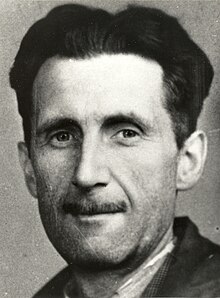

| George Orwell |

|

| Born |

Eric Arthur Blair

25 June 1903

Motihari, Bengal Presidency, British India

(now East Champaran, Bihar, India) |

| Died |

21 January 1950 (aged 46)

University College Hospital, London, England, United Kingdom |

| Resting place |

Sutton Courtenay, Oxfordshire, England, United Kingdom |

| Pen name |

George Orwell |

| Occupation |

Novelist, essayist, journalist, critic |

| Alma mater |

Eton College |

| Genre |

Dystopia, roman à clef, satire |

| Subject |

Anti-fascism, anti-Stalinism, democratic socialism, literary criticism, news, polemic |

| Notable works |

Animal Farm

Nineteen Eighty-Four |

| Years active |

1928–1950 |

| Spouse |

Eileen O’Shaughnessy

(m. 1935; her death 1945)

Sonia Brownell

(m. 1949; his death 1950) |

|

| Signature |

|

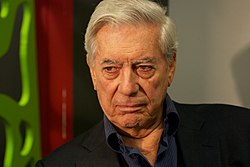

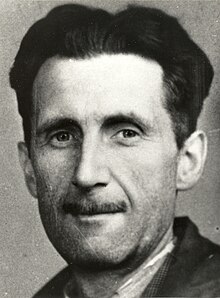

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950),[1] better known by the pen name George Orwell, was an English novelist, essayist, journalist, and critic. His work is marked by lucid prose, awareness of social injustice, opposition to totalitarianism, and outspoken support of democratic socialism.[2][3]

Orwell wrote literary criticism, poetry, fiction, and polemical journalism. He is best known for the allegorical novella Animal Farm (1945) and the dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949). His non-fiction works, including The Road to Wigan Pier (1937), documenting his experience of working class life in the north of England, and Homage to Catalonia (1938), an account of his experiences in the Spanish Civil War, are widely acclaimed, as are his essays on politics, literature, language, and culture. In 2008, The Times ranked him second on a list of “The 50 greatest British writers since 1945”.[4]

Orwell’s work continues to influence popular and political culture, and the term Orwellian – descriptive of totalitarian or authoritarian social practices – has entered the language together with many of his neologisms, including cold war, Big Brother, Thought Police, Room 101, memory hole, newspeak, doublethink, and thoughtcrime.[5]

Life

Early years

Blair family home at Shiplake, Oxfordshire

Eric Arthur Blair was born on 25 June 1903, in Motihari, Bengal Presidency (present-day Bihar), in British India.[6] His great-grandfather Charles Blair was a wealthy country gentleman in Dorset who married Lady Mary Fane, daughter of the Earl of Westmorland, and had income as an absentee landlord of plantations in Jamaica.[7] His grandfather, Thomas Richard Arthur Blair, was a clergyman.[8] Although the gentility passed down the generations, the prosperity did not; Eric Blair described his family as “lower-upper-middle class“.[9] His father, Richard Walmesley Blair, worked in the Opium Department of the Indian Civil Service.[10] His mother, Ida Mabel Blair (née Limouzin), grew up in Moulmein, Burma, where her French father was involved in speculative ventures.[7] Eric had two sisters: Marjorie, five years older, and Avril, five years younger. When Eric was one year old, his mother took him and his sister to England.[11][n 1] His birthplace and ancestral house in Motihari has been declared a protected monument of historical importance.[12]

In 1904, Ida Blair settled with her children at Henley-on-Thames in Oxfordshire. Eric was brought up in the company of his mother and sisters, and apart from a brief visit in mid-1907,[13] they did not see the husband and father Richard Blair until 1912.[8] His mother’s diary from 1905 describes a lively round of social activity and artistic interests.

Before the First World War, the family moved to Shiplake, Oxfordshire where Eric became friendly with the Buddicom family, especially their daughter Jacintha. When they first met, he was standing on his head in a field. On being asked why, he said, “You are noticed more if you stand on your head than if you are right way up.”[14] Jacintha and Eric read and wrote poetry, and dreamed of becoming famous writers. He said that he might write a book in the style of H. G. Wells‘s A Modern Utopia. During this period, he also enjoyed shooting, fishing and birdwatching with Jacintha’s brother and sister.[14]

At the age of five, Eric was sent as a day-boy to a convent school in Henley-on-Thames, which Marjorie also attended. It was a Roman Catholic convent run by French Ursuline nuns, who had been exiled from France after religious education was banned in 1903.[15] His mother wanted him to have a public school education, but his family could not afford the fees, and he needed to earn a scholarship. Ida Blair’s brother Charles Limouzin recommended St Cyprian’s School, Eastbourne, East Sussex.[8] Limouzin, who was a proficient golfer, knew of the school and its headmaster through the Royal Eastbourne Golf Club, where he won several competitions in 1903 and 1904.[16] The headmaster undertook to help Blair to win a scholarship, and made a private financial arrangement that allowed Blair’s parents to pay only half the normal fees. In September 1911 Eric arrived at St Cyprian’s. He boarded at the school for the next five years, returning home only for school holidays. He knew nothing of the reduced fees, although he “soon recognised that he was from a poorer home”.[17] Blair hated the school[18] and many years later wrote an essay “Such, Such Were the Joys“, published posthumously, based on his time there. At St. Cyprian’s, Blair first met Cyril Connolly, who became a writer. Many years later, as the editor of Horizon, Connolly published several of Orwell’s essays.

While at St Cyprian’s, Blair wrote two poems that were published in the Henley and South Oxfordshire Standard.[19][20] He came second to Connolly in the Harrow History Prize, had his work praised by the school’s external examiner, and earned scholarships to Wellington and Eton. But inclusion on the Eton scholarship roll did not guarantee a place, and none was immediately available for Blair. He chose to stay at St Cyprian’s until December 1916, in case a place at Eton became available.[8]

In January, Blair took up the place at Wellington, where he spent the Spring term. In May 1917 a place became available as a King’s Scholar at Eton. He remained at Eton until December 1921, when he left midway between his 18th and 19th birthday. Wellington was “beastly”, Orwell told his childhood friend Jacintha Buddicom, but he said he was “interested and happy” at Eton.[21] His principal tutor was A. S. F. Gow, Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, who also gave him advice later in his career.[8] Blair was briefly taught French by Aldous Huxley. Stephen Runciman, who was at Eton with Blair, noted that he and his contemporaries appreciated Huxley’s linguistic flair.[22] Cyril Connolly followed Blair to Eton, but because they were in separate years, they did not associate with each other.[23]

Blair’s academic performance reports suggest that he neglected his academic studies,[22] but during his time at Eton he worked with Roger Mynors to produce a College magazine, The Election Times, joined in the production of other publications – College Days and Bubble and Squeak – and participated in the Eton Wall Game. His parents could not afford to send him to a university without another scholarship, and they concluded from his poor results that he would not be able to win one. Runciman noted that he had a romantic idea about the East,[22] and the family decided that Blair should join the Imperial Police, the precursor of the Indian Police Service. For this he had to pass an entrance examination. His father had retired to Southwold, Suffolk, by this time; Blair was enrolled at a crammer there called Craighurst, and brushed up on his Classics, English, and History. He passed the entrance exam, coming seventh out of the 26 candidates who exceeded the pass mark.[8][24]

Policing in Burma

Blair pictured in a passport photo during his Burma years

Blair’s maternal grandmother lived at Moulmein, so he chose a posting in Burma. In October 1922 he sailed on board SS Herefordshire via the Suez Canal and Ceylon to join the Indian Imperial Police in Burma. A month later, he arrived at Rangoon and travelled to the police training school in Mandalay. After a short posting at Maymyo, Burma’s principal hill station, he was posted to the frontier outpost of Myaungmya in the Irrawaddy Delta at the beginning of 1924.

Working as an imperial policeman gave him considerable responsibility while most of his contemporaries were still at university in England. When he was posted farther east in the Delta to Twante as a sub-divisional officer, he was responsible for the security of some 200,000 people. At the end of 1924, he was promoted to Assistant District Superintendent and posted to Syriam, closer to Rangoon. Syriam had the refinery of the Burmah Oil Company, “the surrounding land a barren waste, all vegetation killed off by the fumes of sulphur dioxide pouring out day and night from the stacks of the refinery.” But the town was near Rangoon, a cosmopolitan seaport, and Blair went into the city as often as he could, “to browse in a bookshop; to eat well-cooked food; to get away from the boring routine of police life”.[25] In September 1925 he went to Insein, the home of Insein Prison, the second largest jail in Burma. In Insein, he had “long talks on every conceivable subject” with Elisa Maria Langford-Rae (who later married Kazi Lhendup Dorjee). She noted his “sense of utter fairness in minutest details”.[26]

British Club in Katha (in Orwell’s time, it occupied only the ground floor)

In April 1926 he moved to Moulmein, where his maternal grandmother lived. At the end of that year, he was assigned to Katha in Upper Burma, where he contracted dengue fever in 1927. Entitled to a leave in England that year, he was allowed to return in July due to his illness. While on leave in England and on holiday with his family in Cornwall in September 1927, he reappraised his life. Deciding against returning to Burma, he resigned from the Indian Imperial Police to become a writer. He drew on his experiences in the Burma police for the novel Burmese Days (1934) and the essays “A Hanging” (1931) and “Shooting an Elephant” (1936).

In Burma, Blair acquired a reputation as an outsider. He spent much of his time alone, reading or pursuing non-pukka activities, such as attending the churches of the Karen ethnic group. A colleague, Roger Beadon, recalled (in a 1969 recording for the BBC) that Blair was fast to learn the language and that before he left Burma, “was able to speak fluently with Burmese priests in ‘very high-flown Burmese.'”[27] Blair made changes to his appearance in Burma that remained for the rest of his life. “While in Burma, he acquired a moustache similar to those worn by officers of the British regiments stationed there. [He] also acquired some tattoos; on each knuckle he had a small untidy blue circle. Many Burmese living in rural areas still sport tattoos like this – they are believed to protect against bullets and snake bites.”[28] Later, he wrote that he felt guilty about his role in the work of empire and he “began to look more closely at his own country and saw that England also had its oppressed …”

London and Paris

In England, he settled back in the family home at Southwold, renewing acquaintance with local friends and attending an Old Etonian dinner. He visited his old tutor Gow at Cambridge for advice on becoming a writer.[29] In 1927 he moved to London.[30] Ruth Pitter, a family acquaintance, helped him find lodgings, and by the end of 1927 he had moved into rooms in Portobello Road;[31] a blue plaque commemorates his residence there.[32] Pitter’s involvement in the move “would have lent it a reassuring respectability in Mrs Blair’s eyes.” Pitter had a sympathetic interest in Blair’s writing, pointed out weaknesses in his poetry, and advised him to write about what he knew. In fact he decided to write of “certain aspects of the present that he set out to know” and “ventured into the East End of London – the first of the occasional sorties he would make to discover for himself the world of poverty and the down-and-outers who inhabit it. He had found a subject. These sorties, explorations, expeditions, tours or immersions were made intermittently over a period of five years.”[33]

In imitation of Jack London, whose writing he admired (particularly The People of the Abyss), Blair started to explore the poorer parts of London. On his first outing he set out to Limehouse Causeway, spending his first night in a common lodging house, possibly George Levy’s ‘kip’. For a while he “went native” in his own country, dressing like a tramp, adopting the name P. S. Burton and making no concessions to middle-class mores and expectations; he recorded his experiences of the low life for use in “The Spike“, his first published essay in English, and in the second half of his first book, Down and Out in Paris and London (1933).

In early 1928 he moved to Paris. He lived in the rue du Pot de Fer, a working class district in the 5th Arrondissement.[8] His aunt Nellie Limouzin also lived in Paris and gave him social and, when necessary, financial support. He began to write novels, including an early version of Burmese Days, but nothing else survives from that period.[8] He was more successful as a journalist and published articles in Monde, a political/literary journal edited by Henri Barbusse (his first article as a professional writer, “La Censure en Angleterre”, appeared in that journal on 6 October 1928); G. K.’s Weekly, where his first article to appear in England, “A Farthing Newspaper”, was printed on 29 December 1928;[34] and Le Progrès Civique (founded by the left-wing coalition Le Cartel des Gauches). Three pieces appeared in successive weeks in Le Progrès Civique: discussing unemployment, a day in the life of a tramp, and the beggars of London, respectively. “In one or another of its destructive forms, poverty was to become his obsessive subject – at the heart of almost everything he wrote until Homage to Catalonia.”[35]

He fell seriously ill in February 1929 and was taken to the Hôpital Cochin in the 14th arrondissement, a free hospital where medical students were trained. His experiences there were the basis of his essay “How the Poor Die“, published in 1946. He chose not to identify the hospital, and indeed was deliberately misleading about its location. Shortly afterwards, he had all his money stolen from his lodging house. Whether through necessity or to collect material, he undertook menial jobs like dishwashing in a fashionable hotel on the rue de Rivoli, which he later described in Down and Out in Paris and London. In August 1929, he sent a copy of “The Spike” to John Middleton Murry‘s New Adelphi magazine in London. The magazine was edited by Max Plowman and Sir Richard Rees, and Plowman accepted the work for publication.

Southwold

In December 1929, after nearly two years in Paris, Blair returned to England and went directly to his parents’ house in Southwold, which remained his base for the next five years. The family was well established in the town and his sister Avril was running a tea-house there. He became acquainted with many local people, including Brenda Salkeld, the clergyman’s daughter who worked as a gym-teacher at St Felix Girls’ School, Southwold. Although Salkeld rejected his offer of marriage, she remained a friend and regular correspondent for many years. He also renewed friendships with older friends, such as Dennis Collings, whose girlfriend Eleanor Jacques was also to play a part in his life.[8]

In early 1930 he stayed briefly in Bramley, Leeds, with his sister Marjorie and her husband Humphrey Dakin, who was as unappreciative of Blair as when they knew each other as children. Blair was writing reviews for Adelphi and acting as a private tutor to a disabled child at Southwold. He then became tutor to three young brothers, one of whom, Richard Peters, later became a distinguished academic.[36] “His history in these years is marked by dualities and contrasts. There is Blair leading a respectable, outwardly eventless life at his parents’ house in Southwold, writing; then in contrast, there is Blair as Burton (the name he used in his down-and-out episodes) in search of experience in the kips and spikes, in the East End, on the road, and in the hop fields of Kent.”[37] He went painting and bathing on the beach, and there he met Mabel and Francis Fierz, who later influenced his career. Over the next year he visited them in London, often meeting their friend Max Plowman. He also often stayed at the homes of Ruth Pitter and Richard Rees, where he could “change” for his sporadic tramping expeditions. One of his jobs was domestic work at a lodgings for half a crown (two shillings and sixpence, or one-eighth of a pound) a day.[38]

Blair now contributed regularly to Adelphi, with “A Hanging” appearing in August 1931. From August to September 1931 his explorations of poverty continued, and, like the protagonist of A Clergyman’s Daughter, he followed the East End tradition of working in the Kent hop fields. He kept a diary about his experiences there. Afterwards, he lodged in the Tooley Street kip, but could not stand it for long, and with financial help from his parents moved to Windsor Street, where he stayed until Christmas. “Hop Picking”, by Eric Blair, appeared in the October 1931 issue of New Statesman, whose editorial staff included his old friend Cyril Connolly. Mabel Fierz put him in contact with Leonard Moore, who became his literary agent.

At this time Jonathan Cape rejected A Scullion’s Diary, the first version of Down and Out. On the advice of Richard Rees, he offered it to Faber and Faber, but their editorial director, T. S. Eliot, also rejected it. Blair ended the year by deliberately getting himself arrested,[39] so that he could experience Christmas in prison, but the authorities did not regard his “drunk and disorderly” behaviour as imprisonable, and he returned home to Southwold after two days in a police cell.

Teaching career

In April 1932 Blair became a teacher at The Hawthorns High School, a school for boys in Hayes, West London. This was a small school offering private schooling for children of local tradesmen and shopkeepers, and had only 14 or 16 boys aged between ten and sixteen, and one other master.[40] While at the school he became friendly with the curate of the local parish church and became involved with activities there. Mabel Fierz had pursued matters with Moore, and at the end of June 1932, Moore told Blair that Victor Gollancz was prepared to publish A Scullion’s Diary for a £40 advance, through his recently founded publishing house, Victor Gollancz Ltd, which was an outlet for radical and socialist works.

At the end of the summer term in 1932, Blair returned to Southwold, where his parents had used a legacy to buy their own home. Blair and his sister Avril spent the holidays making the house habitable while he also worked on Burmese Days.[41] He was also spending time with Eleanor Jacques, but her attachment to Dennis Collings remained an obstacle to his hopes of a more serious relationship.

The pen name “George Orwell” was inspired by the River Orwell in the English county of Suffolk[42]

“Clink”, an essay describing his failed attempt to get sent to prison, appeared in the August 1932 number of Adelphi. He returned to teaching at Hayes and prepared for the publication of his book, now known as Down and Out in Paris and London. He wished to publish under a different name to avoid any embarrassment to his family over his time as a “tramp”.[43] In a letter to Moore (dated 15 November 1932), he left the choice of pseudonym to Moore and to Gollancz. Four days later, he wrote to Moore, suggesting the pseudonyms P. S. Burton (a name he used when tramping), Kenneth Miles, George Orwell, and H. Lewis Allways.[44] He finally adopted the nom de plume George Orwell because, as he told Eleanor Jacques, “It is a good round English name.” Down and Out in Paris and London was published on 9 January 1933, as Orwell continued to work on Burmese Days. Down and Out was successful and was next published by Harper & Brothers in New York.

In mid-1933 Blair left Hawthorns to become a teacher at Frays College, in Uxbridge, Middlesex. This was a much larger establishment with 200 pupils and a full complement of staff. He acquired a motorcycle and took trips through the surrounding countryside. On one of these expeditions he became soaked and caught a chill that developed into pneumonia. He was taken to Uxbridge Cottage Hospital, where for a time his life was believed to be in danger. When he was discharged in January 1934, he returned to Southwold to convalesce and, supported by his parents, never returned to teaching.

He was disappointed when Gollancz turned down Burmese Days, mainly on the grounds of potential suits for libel, but Harper were prepared to publish it in the United States. Meanwhile, Blair started work on the novel A Clergyman’s Daughter, drawing upon his life as a teacher and on life in Southwold. Eleanor Jacques was now married and had gone to Singapore and Brenda Salkield had left for Ireland, so Blair was relatively isolated in Southwold – working on the allotments, walking alone and spending time with his father. Eventually in October, after sending A Clergyman’s Daughter to Moore, he left for London to take a job that had been found for him by his aunt Nellie Limouzin.

Hampstead

Orwell’s former home at 77 Parliament Hill, Hampstead, London

This job was as a part-time assistant in Booklovers’ Corner, a second-hand bookshop in Hampstead run by Francis and Myfanwy Westrope, who were friends of Nellie Limouzin in the Esperanto movement. The Westropes were friendly and provided him with comfortable accommodation at Warwick Mansions, Pond Street. He was sharing the job with Jon Kimche, who also lived with the Westropes. Blair worked at the shop in the afternoons and had his mornings free to write and his evenings free to socialise. These experiences provided background for the novel Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1936). As well as the various guests of the Westropes, he was able to enjoy the company of Richard Rees and the Adelphi writers and Mabel Fierz. The Westropes and Kimche were members of the Independent Labour Party, although at this time Blair was not seriously politically active. He was writing for the Adelphi and preparing A Clergyman’s Daughter and Burmese Days for publication.

At the beginning of 1935 he had to move out of Warwick Mansions, and Mabel Fierz found him a flat in Parliament Hill. A Clergyman’s Daughter was published on 11 March 1935. In early 1935 Blair met his future wife Eileen O’Shaughnessy, when his landlady, Rosalind Obermeyer, who was studying for a master’s degree in psychology at University College London, invited some of her fellow students to a party. One of these students, Elizaveta Fen, a biographer and future translator of Chekhov, recalled Orwell and his friend Richard Rees “draped” at the fireplace, looking, she thought, “moth-eaten and prematurely aged.”[45] Around this time, Blair had started to write reviews for the New English Weekly.

Orwell’s time as a bookseller is commemorated with this plaque in Hampstead

In June, Burmese Days was published and Cyril Connolly’s review in the New Statesman prompted Orwell (as he then became known) to re-establish contact with his old friend. In August, he moved into a flat in Kentish Town, which he shared with Michael Sayers and Rayner Heppenstall. The relationship was sometimes awkward and Orwell and Heppenstall even came to blows, though they remained friends and later worked together on BBC broadcasts.[46] Orwell was now working on Keep the Aspidistra Flying, and also tried unsuccessfully to write a serial for the News Chronicle. By October 1935 his flatmates had moved out and he was struggling to pay the rent on his own. He remained until the end of January 1936, when he stopped working at Booklovers’ Corner.

The Road to Wigan Pier

At this time, Victor Gollancz suggested Orwell spend a short time investigating social conditions in economically depressed northern England.[n 2] Two years earlier J. B. Priestley had written about England north of the Trent, sparking an interest in reportage. The depression had also introduced a number of working-class writers from the North of England to the reading public.

On 31 January 1936, Orwell set out by public transport and on foot, reaching Manchester via Coventry, Stafford, the Potteries and Macclesfield. Arriving in Manchester after the banks had closed, he had to stay in a common lodging-house. The next day he picked up a list of contacts sent by Richard Rees. One of these, the trade union official Frank Meade, suggested Wigan, where Orwell spent February staying in dirty lodgings over a tripe shop. At Wigan, he visited many homes to see how people lived, took detailed notes of housing conditions and wages earned, went down Bryn Hall coal mine, and used the local public library to consult public health records and reports on working conditions in mines.

During this time, he was distracted by concerns about style and possible libel in Keep the Aspidistra Flying. He made a quick visit to Liverpool and during March, stayed in south Yorkshire, spending time in Sheffield and Barnsley. As well as visiting mines, including Grimethorpe, and observing social conditions, he attended meetings of the Communist Party and of Oswald Mosley – “his speech the usual claptrap – The blame for everything was put upon mysterious international gangs of Jews” – where he saw the tactics of the Blackshirts – “one is liable to get both a hammering and a fine for asking a question which Mosley finds it difficult to answer.”[48] He also made visits to his sister at Headingley, during which he visited the Brontë Parsonage at Haworth, where he was “chiefly impressed by a pair of Charlotte Brontë‘s cloth-topped boots, very small, with square toes and lacing up at the sides.”[49]

A former warehouse at Wigan Pier is named after Orwell

The result of his journeys through the north was The Road to Wigan Pier, published by Gollancz for the Left Book Club in 1937. The first half of the book documents his social investigations of Lancashire and Yorkshire, including an evocative description of working life in the coal mines. The second half is a long essay on his upbringing and the development of his political conscience, which includes an argument for Socialism (although he goes to lengths to balance the concerns and goals of Socialism with the barriers it faced from the movement’s own advocates at the time, such as ‘priggish’ and ‘dull’ Socialist intellectuals, and ‘proletarian’ Socialists with little grasp of the actual ideology). Gollancz feared the second half would offend readers and added a disculpatory preface to the book while Orwell was in Spain.

Orwell needed somewhere he could concentrate on writing his book, and once again help was provided by Aunt Nellie, who was living at Wallington, Hertfordshire in a very small 16th-century cottage called the “Stores”. Wallington was a tiny village 35 miles north of London, and the cottage had almost no modern facilities. Orwell took over the tenancy and moved in on 2 April 1936.[50] He started work on The Road to Wigan Pier by the end of April, but also spent hours working on the garden and testing the possibility of reopening the Stores as a village shop. Keep the Aspidistra Flying was published by Gollancz on 20 April 1936. On 4 August Orwell gave a talk at the Adelphi Summer School held at Langham, entitled An Outsider Sees the Distressed Areas; others who spoke at the school included John Strachey, Max Plowman, Karl Polanyi and Reinhold Niebuhr.

Orwell’s research for The Road to Wigan Pier led to him being placed under surveillance by the Special Branch from 1936, for 12 years, until one year before the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four.[51]

Orwell married Eileen O’Shaughnessy on 9 June 1936. Shortly afterwards, the political crisis began in Spain and Orwell followed developments there closely. At the end of the year, concerned by Francisco Franco‘s military uprising, (supported by Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy and local groups such as Falange), Orwell decided to go to Spain to take part in the Spanish Civil War on the Republican side. Under the erroneous impression that he needed papers from some left-wing organisation to cross the frontier, on John Strachey‘s recommendation he applied unsuccessfully to Harry Pollitt, leader of the British Communist Party. Pollitt was suspicious of Orwell’s political reliability; he asked him whether he would undertake to join the International Brigade and advised him to get a safe-conduct from the Spanish Embassy in Paris.[52] Not wishing to commit himself until he had seen the situation in situ, Orwell instead used his Independent Labour Party contacts to get a letter of introduction to John McNair in Barcelona.

The Spanish Civil War

The square in Barcelona renamed in Orwell’s honour

Orwell set out for Spain on about 23 December 1936, dining with Henry Miller in Paris on the way. The American writer told Orwell that going to fight in the Civil War out of some sense of obligation or guilt was ‘sheer stupidity,’ and that the Englishman’s ideas ‘about combating Fascism, defending democracy, etc., etc., were all baloney.’[53] A few days later, in Barcelona, Orwell met John McNair of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) Office who quoted him: “I’ve come to fight against Fascism”.[54] Orwell stepped into a complex political situation in Catalonia. The Republican government was supported by a number of factions with conflicting aims, including the Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification (POUM – Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista), the anarcho-syndicalist Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) and the Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia (a wing of the Spanish Communist Party, which was backed by Soviet arms and aid). The ILP was linked to the POUM so Orwell joined the POUM.

After a time at the Lenin Barracks in Barcelona he was sent to the relatively quiet Aragon Front under Georges Kopp. By January 1937 he was at Alcubierre 1,500 feet (460 m) above sea level, in the depth of winter. There was very little military action, and Orwell was shocked by the lack of munitions, food, and firewood, and other extreme deprivations.[55] Orwell, with his Cadet Corps and police training, was quickly made a corporal. On the arrival of a British ILP Contingent about three weeks later, Orwell and the other English militiaman, Williams, were sent with them to Monte Oscuro. The newly arrived ILP contingent included Bob Smillie, Bob Edwards, Stafford Cottman and Jack Branthwaite. The unit was then sent on to Huesca.

Meanwhile, back in England, Eileen had been handling the issues relating to the publication of The Road to Wigan Pier before setting out for Spain herself, leaving Nellie Limouzin to look after The Stores. Eileen volunteered for a post in John McNair’s office and with the help of Georges Kopp paid visits to her husband, bringing him English tea, chocolate, and cigars.[56] Orwell had to spend some days in hospital with a poisoned hand[57] and had most of his possessions stolen by the staff. He returned to the front and saw some action in a night attack on the Nationalist trenches where he chased an enemy soldier with a bayonet and bombed an enemy rifle position.

In April, Orwell returned to Barcelona.[57] Wanting to be sent to the Madrid front, which meant he “must join the International Column”, he approached a Communist friend attached to the Spanish Medical Aid and explained his case. “Although he did not think much of the Communists, Orwell was still ready to treat them as friends and allies. That would soon change.”[58] This was the time of the Barcelona May Days and Orwell was caught up in the factional fighting. He spent much of the time on a roof, with a stack of novels, but encountered Jon Kimche from his Hampstead days during the stay. The subsequent campaign of lies and distortion carried out by the Communist press,[59] in which the POUM was accused of collaborating with the fascists, had a dramatic effect on Orwell. Instead of joining the International Brigades as he had intended, he decided to return to the Aragon Front. Once the May fighting was over, he was approached by a Communist friend who asked if he still intended transferring to the International Brigades. Orwell expressed surprise that they should still want him, because according to the Communist press he was a fascist.[60] “No one who was in Barcelona then, or for months later, will forget the horrible atmosphere produced by fear, suspicion, hatred, censored newspapers, crammed jails, enormous food queues and prowling gangs of armed men.”[61]

After his return to the front, he was wounded in the throat by a sniper’s bullet. At 6 ft 2 in (1.88 m) Orwell was considerably taller than the Spanish fighters[62] and had been warned against standing against the trench parapet. Unable to speak, and with blood pouring from his mouth, Orwell was carried on a stretcher to Siétamo, loaded on an ambulance and after a bumpy journey via Barbastro arrived at the hospital at Lérida. He recovered sufficiently to get up and on 27 May 1937 was sent on to Tarragona and two days later to a POUM sanatorium in the suburbs of Barcelona. The bullet had missed his main artery by the barest margin and his voice was barely audible. It had been such a clean shot that the wound immediately went through the process of cauterisation. He received electrotherapy treatment and was declared medically unfit for service.[63]

By the middle of June the political situation in Barcelona had deteriorated and the POUM – painted by the pro-Soviet Communists as a Trotskyist organisation – was outlawed and under attack. The Communist line was that the POUM were “objectively” Fascist, hindering the Republican cause. “A particularly nasty poster appeared, showing a head with a POUM mask being ripped off to reveal a Swastika-covered face beneath.”[64] Members, including Kopp, were arrested and others were in hiding. Orwell and his wife were under threat and had to lie low,[n 3] although they broke cover to try to help Kopp.

Finally with their passports in order, they escaped from Spain by train, diverting to Banyuls-sur-Mer for a short stay before returning to England. In the first week of July 1937 Orwell arrived back at Wallington; on 13 July 1937 a deposition was presented to the Tribunal for Espionage & High Treason, Valencia, charging the Orwells with “rabid Trotskyism“, and being agents of the POUM.[65] The trial of the leaders of the POUM and of Orwell (in his absence) took place in Barcelona in October and November 1938. Observing events from French Morocco, Orwell wrote that they were ” – only a by-product of the Russian Trotskyist trials and from the start every kind of lie, including flagrant absurdities, has been circulated in the Communist press.”[66] Orwell’s experiences in the Spanish Civil War gave rise to Homage to Catalonia (1938).

Rest and recuperation

Laurence O’Shaughnessy’s former home, the large house on the corner, 24 Crooms Hill, Greenwich, London[67]

Orwell returned to England in June 1937, and stayed at the O’Shaughnessy home at Greenwich. He found his views on the Spanish Civil War out of favour. Kingsley Martin rejected two of his works and Gollancz was equally cautious. At the same time, the communist Daily Worker was running an attack on The Road to Wigan Pier, misquoting Orwell as saying “the working classes smell”; a letter to Gollancz from Orwell threatening libel action brought a stop to this. Orwell was also able to find a more sympathetic publisher for his views in Frederic Warburg of Secker & Warburg. Orwell returned to Wallington, which he found in disarray after his absence. He acquired goats, a rooster he called “Henry Ford”, and a poodle puppy he called “Marx”[68][69][70] and settled down to animal husbandry and writing Homage to Catalonia.

There were thoughts of going to India to work on the Pioneer, a newspaper in Lucknow, but by March 1938 Orwell’s health had deteriorated. He was admitted to Preston Hall Sanatorium at Aylesford, Kent, a British Legion hospital for ex-servicemen to which his brother-in-law Laurence O’Shaughnessy was attached. He was thought initially to be suffering from tuberculosis and stayed in the sanatorium until September. A stream of visitors came to see him including Common, Heppenstall, Plowman and Cyril Connolly. Connolly brought with him Stephen Spender, a cause of some embarrassment as Orwell had referred to Spender as a “pansy friend” some time earlier. Homage to Catalonia was published by Secker & Warburg and was a commercial flop. In the latter part of his stay at the clinic Orwell was able to go for walks in the countryside and study nature.

The novelist L. H. Myers secretly funded a trip to French Morocco for half a year for Orwell to avoid the English winter and recover his health. The Orwells set out in September 1938 via Gibraltar and Tangier to avoid Spanish Morocco and arrived at Marrakech. They rented a villa on the road to Casablanca and during that time Orwell wrote Coming Up for Air. They arrived back in England on 30 March 1939 and Coming Up for Air was published in June. Orwell spent time in Wallington and Southwold working on a Dickens essay and it was in July 1939 that Orwell’s father, Richard Blair, died.

Second World War and Animal Farm

At the outbreak of the Second World War, Orwell’s wife Eileen started working in the Censorship Department of the Ministry of Information in central London, staying during the week with her family in Greenwich. Orwell also submitted his name to the Central Register for war work, but nothing transpired. “They won’t have me in the army, at any rate at present, because of my lungs”, Orwell told Geoffrey Gorer. He returned to Wallington, and in late 1939 he wrote material for his first collection of essays, Inside the Whale. For the next year he was occupied writing reviews for plays, films and books for The Listener, Time and Tide and New Adelphi. On 29 March 1940 his long association with Tribune began[71] with a review of a sergeant’s account of Napoleon‘s retreat from Moscow. At the beginning of 1940, the first edition of Connolly’s Horizon appeared, and this provided a new outlet for Orwell’s work as well as new literary contacts. In May the Orwells took lease of a flat in London at Dorset Chambers, Chagford Street, Marylebone. It was the time of the Dunkirk evacuation and the death in France of Eileen’s brother Lawrence caused her considerable grief and long-term depression. Throughout this period Orwell kept a wartime diary.

Orwell was declared “unfit for any kind of military service” by the Medical Board in June, but soon afterwards found an opportunity to become involved in war activities by joining the Home Guard. He shared Tom Wintringham‘s socialist vision for the Home Guard as a revolutionary People’s Militia. His lecture notes for instructing platoon members include advice on street fighting, field fortifications, and the use of mortars of various kinds. Sergeant Orwell managed to recruit Frederic Warburg to his unit. During the Battle of Britain he used to spend weekends with Warburg and his new Zionist friend, Tosco Fyvel, at Warburg’s house at Twyford, Berkshire. At Wallington he worked on “England Your England” and in London wrote reviews for various periodicals. Visiting Eileen’s family in Greenwich brought him face-to-face with the effects of the blitz on East London. In mid-1940, Warburg, Fyvel and Orwell planned Searchlight Books. Eleven volumes eventually appeared, of which Orwell’s The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius, published on 19 February 1941, was the first.[72]

Early in 1941 he started writing for the American Partisan Review which linked Orwell with The New York Intellectuals, like him anti-Stalinist, but committed to staying on the Left,[73] and contributed to Gollancz anthology The Betrayal of the Left, written in the light of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact (although Orwell referred to it as the Russo-German Pact and the Hitler-Stalin Pact[74]). He also applied unsuccessfully for a job at the Air Ministry. Meanwhile, he was still writing reviews of books and plays and at this time met the novelist Anthony Powell. He also took part in a few radio broadcasts for the Eastern Service of the BBC. In March the Orwells moved to a seventh-floor flat at Langford Court, St John’s Wood, while at Wallington Orwell was “digging for victory” by planting potatoes.

One could not have a better example of the moral and emotional shallowness of our time, than the fact that we are now all more or less pro Stalin. This disgusting murderer is temporarily on our side, and so the purges, etc., are suddenly forgotten.

— George Orwell, in his war-time diary, 3 July 1941[75]

In August 1941, Orwell finally obtained “war work” when he was taken on full-time by the BBC’s Eastern Service. He supervised cultural broadcasts to India to counter propaganda from Nazi Germany designed to undermine Imperial links. This was Orwell’s first experience of the rigid conformity of life in an office, and it gave him an opportunity to create cultural programmes with contributions from T. S. Eliot, Dylan Thomas, E. M. Forster, Ahmed Ali, Mulk Raj Anand, and William Empson among others.

At the end of August he had a dinner with H. G. Wells which degenerated into a row because Wells had taken offence at observations Orwell made about him in a Horizon article. In October Orwell had a bout of bronchitis and the illness recurred frequently. David Astor was looking for a provocative contributor for The Observer and invited Orwell to write for him – the first article appearing in March 1942. In early 1942 Eileen changed jobs to work at the Ministry of Food and in mid-1942 the Orwells moved to a larger flat, a ground floor and basement, 10a Mortimer Crescent in Maida Vale/Kilburn – “the kind of lower-middle-class ambience that Orwell thought was London at its best.” Around the same time Orwell’s mother and sister Avril, who had found work in a sheet-metal factory behind Kings Cross Station, moved into a flat close to George and Eileen.[76]

Orwell at the BBC in 1941. Despite having spoken on many broadcasts, no recordings of Orwell’s voice are known to survive.[77][78][79]

At the BBC, Orwell introduced Voice, a literary programme for his Indian broadcasts, and by now was leading an active social life with literary friends, particularly on the political left. Late in 1942, he started writing regularly for the left-wing weekly Tribune[80]:306[81]:441 directed by Labour MPs Aneurin Bevan and George Strauss. In March 1943 Orwell’s mother died and around the same time he told Moore he was starting work on a new book, which turned out to be Animal Farm.

In September 1943, Orwell resigned from the BBC post that he had occupied for two years.[82]:352 His resignation followed a report confirming his fears that few Indians listened to the broadcasts,[83] but he was also keen to concentrate on writing Animal Farm. Just six days before his last day of service, on 24 November 1943, his adaptation of the fairy tale, Hans Christian Andersen‘s The Emperor’s New Clothes was broadcast. It was a genre in which he was greatly interested and which appeared on Animal Farm‘s title-page.[84] At this time he also resigned from the Home Guard on medical grounds.[85]

In November 1943, Orwell was appointed literary editor at Tribune, where his assistant was his old friend Jon Kimche. Orwell was on staff until early 1945, writing over 80 book reviews[86] and on 3 December 1943 started his regular personal column, “As I Please“, usually addressing three or four subjects in each.[87] He was still writing reviews for other magazines, including Partisan Review, Horizon, and the New York Nation and becoming a respected pundit among left-wing circles but also a close friend of people on the right such as Powell, Astor and Malcolm Muggeridge. By April 1944 Animal Farm was ready for publication. Gollancz refused to publish it, considering it an attack on the Soviet regime which was a crucial ally in the war. A similar fate was met from other publishers (including T. S. Eliot at Faber and Faber) until Jonathan Cape agreed to take it.

In May the Orwells had the opportunity to adopt a child, thanks to the contacts of Eileen’s sister Gwen O’Shaughnessy, then a doctor in Newcastle upon Tyne. In June a V-1 flying bomb struck Mortimer Crescent and the Orwells had to find somewhere else to live. Orwell had to scrabble around in the rubble for his collection of books, which he had finally managed to transfer from Wallington, carting them away in a wheelbarrow.

Another bombshell was Cape’s reversal of his plan to publish Animal Farm. The decision followed his personal visit to Peter Smollett, an official at the Ministry of Information. Smollett was later identified as a Soviet agent.[88][89]

The Orwells spent some time in the North East, near Carlton, County Durham, dealing with matters in the adoption of a boy whom they named Richard Horatio Blair.[90] By September 1944 they had set up home in Islington, at 27b Canonbury Square.[91] Baby Richard joined them there, and Eileen gave up her work at the Ministry of Food to look after her family. Secker & Warburg had agreed to publish Animal Farm, planned for the following March, although it did not appear in print until August 1945. By February 1945 David Astor had invited Orwell to become a war correspondent for the Observer. Orwell had been looking for the opportunity throughout the war, but his failed medical reports prevented him from being allowed anywhere near action. He went to Paris after the liberation of France and to Cologne once it had been occupied by the Allies.

It was while he was there that Eileen went into hospital for a hysterectomy and died under anaesthetic on 29 March 1945. She had not given Orwell much notice about this operation because of worries about the cost and because she expected to make a speedy recovery. Orwell returned home for a while and then went back to Europe. He returned finally to London to cover the 1945 general election at the beginning of July. Animal Farm: A Fairy Story was published in Britain on 17 August 1945, and a year later in the US, on 26 August 1946.

Jura and Nineteen Eighty-Four

Animal Farm struck a particular resonance in the post-war climate and its worldwide success made Orwell a sought-after figure.

For the next four years Orwell mixed journalistic work – mainly for Tribune, The Observer and the Manchester Evening News, though he also contributed to many small-circulation political and literary magazines – with writing his best-known work, Nineteen Eighty-Four, which was published in 1949.

Barnhill on the Isle of Jura off the west coast of Scotland

In the year following Eileen’s death he published around 130 articles and a selection of his Critical Essays, while remaining active in various political lobbying campaigns. He employed a housekeeper, Susan Watson, to look after his adopted son at the Islington flat, which visitors now described as “bleak”. In September he spent a fortnight on the island of Jura in the Inner Hebrides and saw it as a place to escape from the hassle of London literary life. David Astor was instrumental in arranging a place for Orwell on Jura.[92] Astor’s family owned Scottish estates in the area and a fellow Old Etonian Robin Fletcher had a property on the island. In late 1945 and early 1946 Orwell made several hopeless and unwelcome marriage proposals to younger women, including Celia Kirwan (who was later to become Arthur Koestler‘s sister-in-law), Ann Popham who happened to live in the same block of flats and Sonia Brownell, one of Connolly’s coterie at the Horizon office. Orwell suffered a tubercular haemorrhage in February 1946 but disguised his illness. In 1945 or early 1946, while still living at Canonbury Square, Orwell wrote an article on “British Cookery”, complete with recipes, commissioned by the British Council. Given the post-war shortages, both parties agreed not to publish it.[93] His sister Marjorie died of kidney disease in May and shortly after, on 22 May 1946, Orwell set off to live on the Isle of Jura.

Barnhill[94] was an abandoned farmhouse with outbuildings near the northern end of the island, situated at the end of a five-mile (8 km), heavily rutted track from Ardlussa, where the owners lived. Conditions at the farmhouse were primitive but the natural history and the challenge of improving the place appealed to Orwell. His sister Avril accompanied him there and young novelist Paul Potts made up the party. In July Susan Watson arrived with Orwell’s son Richard. Tensions developed and Potts departed after one of his manuscripts was used to light the fire. Orwell meanwhile set to work on Nineteen Eighty-Four. Later Susan Watson’s boyfriend David Holbrook arrived. A fan of Orwell since school days, he found the reality very different, with Orwell hostile and disagreeable probably because of Holbrook’s membership of the Communist Party.[95] Susan Watson could no longer stand being with Avril and she and her boyfriend left.

Orwell returned to London in late 1946 and picked up his literary journalism again. Now a well-known writer, he was swamped with work. Apart from a visit to Jura in the new year he stayed in London for one of the coldest British winters on record and with such a national shortage of fuel that he burnt his furniture and his child’s toys. The heavy smog in the days before the Clean Air Act 1956 did little to help his health about which he was reticent, keeping clear of medical attention. Meanwhile, he had to cope with rival claims of publishers Gollancz and Warburg for publishing rights. About this time he co-edited a collection titled British Pamphleteers with Reginald Reynolds. As a result of the success of Animal Farm, Orwell was expecting a large bill from the Inland Revenue and he contacted a firm of accountants of which the senior partner was Jack Harrison. The firm advised Orwell to establish a company to own his copyright and to receive his royalties and set up a “service agreement” so that he could draw a salary. Such a company “George Orwell Productions Ltd” (GOP Ltd) was set up on 12 September 1947 although the service agreement was not then put into effect. Jack Harrison left the details at this stage to junior colleagues.[96]

Orwell left London for Jura on 10 April 1947.[8] In July he ended the lease on the Wallington cottage.[97] Back on Jura he worked on Nineteen Eighty-Four and made good progress. During that time his sister’s family visited, and Orwell led a disastrous boating expedition, on 19 August,[98] which nearly led to loss of life whilst trying to cross the notorious gulf of Corryvreckan and gave him a soaking which was not good for his health. In December a chest specialist was summoned from Glasgow who pronounced Orwell seriously ill and a week before Christmas 1947 he was in Hairmyres Hospital in East Kilbride, then a small village in the countryside, on the outskirts of Glasgow. Tuberculosis was diagnosed and the request for permission to import streptomycin to treat Orwell went as far as Aneurin Bevan, then Minister of Health. David Astor helped with supply and payment and Orwell began his course of streptomycin on 19 or 20 February 1948.[99] By the end of July 1948 Orwell was able to return to Jura and by December he had finished the manuscript of Nineteen Eighty-Four. In January 1949, in a very weak condition, he set off for a sanatorium at Cranham, Gloucestershire, escorted by Richard Rees.

The sanatorium at Cranham consisted of a series of small wooden chalets or huts in a remote part of the Cotswolds near Stroud. Visitors were shocked by Orwell’s appearance and concerned by the short-comings and ineffectiveness of the treatment. Friends were worried about his finances, but by now he was comparatively well-off. He was writing to many of his friends, including Jacintha Buddicom, who had “rediscovered” him, and in March 1949, was visited by Celia Kirwan. Kirwan had just started working for a Foreign Office unit, the Information Research Department, set up by the Labour government to publish anti-communist propaganda, and Orwell gave her a list of people he considered to be unsuitable as IRD authors because of their pro-communist leanings. Orwell’s list, not published until 2003, consisted mainly of writers but also included actors and Labour MPs.[88][100] Orwell received more streptomycin treatment and improved slightly. In June 1949 Nineteen Eighty-Four was published to immediate critical and popular acclaim.

Final months and death

Orwell’s health had continued to decline since the diagnosis of tuberculosis in December 1947. In mid-1949, he courted Sonia Brownell, and they announced their engagement in September, shortly before he was removed to University College Hospital in London. Sonia took charge of Orwell’s affairs and attended him diligently in the hospital, causing concern to some old friends such as Muggeridge. In September 1949, Orwell invited his accountant Harrison to visit him in hospital, and Harrison claimed that Orwell then asked him to become director of GOP Ltd and to manage the company, but there was no independent witness.[96] Orwell’s wedding took place in the hospital room on 13 October 1949, with David Astor as best man.[101] Orwell was in decline and visited by an assortment of visitors including Muggeridge, Connolly, Lucian Freud, Stephen Spender, Evelyn Waugh, Paul Potts, Anthony Powell, and his Eton tutor Anthony Gow.[8] Plans to go to the Swiss Alps were mooted. Further meetings were held with his accountant, at which Harrison and Mr and Mrs Blair were confirmed as directors of the company, and at which Harrison claimed that the “service agreement” was executed, giving copyright to the company.[96] Orwell’s health was in decline again by Christmas. On the evening of 20 January 1950, Potts visited Orwell and slipped away on finding him asleep. Jack Harrison visited later and claimed that Orwell gave him 25% of the company.[96] Early on the morning of 21 January, an artery burst in Orwell’s lungs, killing him at age 46.[102]

Orwell had requested to be buried in accordance with the Anglican rite in the graveyard of the closest church to wherever he happened to die. The graveyards in central London had no space, and fearing that he might have to be cremated against his wishes, his widow appealed to his friends to see whether any of them knew of a church with space in its graveyard.

David Astor lived in Sutton Courtenay, Oxfordshire, and arranged for Orwell to be interred in All Saints’ Churchyard there.[103] Orwell’s gravestone bears the simple epitaph: “Here lies Eric Arthur Blair, born June 25th 1903, died January 21st 1950”; no mention is made on the gravestone of his more famous pen name.

Orwell’s son, Richard Horatio Blair, was brought up by Orwell’s sister Avril. He maintains a public profile as patron of the Orwell Society.[104] He gives interviews about the few memories he has of his father.

In 1979, Sonia Brownell brought a High Court action against Harrison, who had in the meantime transferred 75% of the company’s voting stock to himself and had dissipated much of the value of the company. She was considered to have a strong case, but was becoming increasingly ill and eventually was persuaded to settle out of court on 2 November 1980. She died on 11 December 1980, aged 62.[96]

Literary career and legacy

During most of his career, Orwell was best known for his journalism, in essays, reviews, columns in newspapers and magazines and in his books of reportage: Down and Out in Paris and London (describing a period of poverty in these cities), The Road to Wigan Pier (describing the living conditions of the poor in northern England, and class division generally) and Homage to Catalonia. According to Irving Howe, Orwell was “the best English essayist since Hazlitt, perhaps since Dr Johnson.”[105]

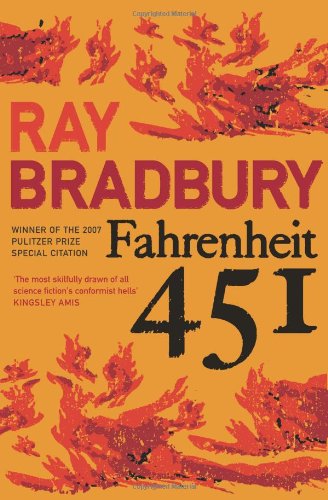

Modern readers are more often introduced to Orwell as a novelist, particularly through his enormously successful titles Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four. The former is often thought to reflect degeneration in the Soviet Union after the Russian Revolution and the rise of Stalinism; the latter, life under totalitarian rule. Nineteen Eighty-Four is often compared to Brave New World by Aldous Huxley; both are powerful dystopian novels warning of a future world where the state machine exerts complete control over social life. In 1984, Nineteen Eighty-Four and Ray Bradbury‘s Fahrenheit 451 were honoured with the Prometheus Award for their contributions to dystopian literature. In 2011 he received it again for Animal Farm.

Coming Up for Air, his last novel before World War II is the most “English” of his novels; alarms of war mingle with images of idyllic Thames-side Edwardian childhood of protagonist George Bowling. The novel is pessimistic; industrialism and capitalism have killed the best of Old England, and there were great, new external threats. In homely terms, Bowling posits the totalitarian hypotheses of Borkenau, Orwell, Silone and Koestler: “Old Hitler’s something different. So’s Joe Stalin. They aren’t like these chaps in the old days who crucified people and chopped their heads off and so forth, just for the fun of it … They’re something quite new – something that’s never been heard of before”.

Literary influences

In an autobiographical piece that Orwell sent to the editors of Twentieth Century Authors in 1940, he wrote: “The writers I care about most and never grow tired of are: Shakespeare, Swift, Fielding, Dickens, Charles Reade, Flaubert and, among modern writers, James Joyce, T. S. Eliot and D. H. Lawrence. But I believe the modern writer who has influenced me most is W. Somerset Maugham, whom I admire immensely for his power of telling a story straightforwardly and without frills.” Elsewhere, Orwell strongly praised the works of Jack London, especially his book The Road. Orwell’s investigation of poverty in The Road to Wigan Pier strongly resembles that of Jack London’s The People of the Abyss, in which the American journalist disguises himself as an out-of-work sailor to investigate the lives of the poor in London. In his essay “Politics vs. Literature: An Examination of Gulliver’s Travels” (1946) Orwell wrote: “If I had to make a list of six books which were to be preserved when all others were destroyed, I would certainly put Gulliver’s Travels among them.”

Other writers admired by Orwell included: Ralph Waldo Emerson, George Gissing, Graham Greene, Herman Melville, Henry Miller, Tobias Smollett, Mark Twain, Joseph Conrad and Yevgeny Zamyatin.[106] He was both an admirer and a critic of Rudyard Kipling,[107][108] praising Kipling as a gifted writer and a “good bad poet” whose work is “spurious” and “morally insensitive and aesthetically disgusting,” but undeniably seductive and able to speak to certain aspects of reality more effectively than more enlightened authors.[109] He had a similarly ambivalent attitude to G. K. Chesterton, whom he regarded as a writer of considerable talent who had chosen to devote himself to “Roman Catholic propaganda”.[110]

Orwell as literary critic

Throughout his life Orwell continually supported himself as a book reviewer, writing works so long and sophisticated they have had an influence on literary criticism. He wrote in the conclusion to his 1940 essay on Charles Dickens,

When one reads any strongly individual piece of writing, one has the impression of seeing a face somewhere behind the page. It is not necessarily the actual face of the writer. I feel this very strongly with Swift, with Defoe, with Fielding, Stendhal, Thackeray, Flaubert, though in several cases I do not know what these people looked like and do not want to know. What one sees is the face that the writer ought to have. Well, in the case of Dickens I see a face that is not quite the face of Dickens’s photographs, though it resembles it. It is the face of a man of about forty, with a small beard and a high colour. He is laughing, with a touch of anger in his laughter, but no triumph, no malignity. It is the face of a man who is always fighting against something, but who fights in the open and is not frightened, the face of a man who is generously angry – in other words, of a nineteenth-century liberal, a free intelligence, a type hated with equal hatred by all the smelly little orthodoxies which are now contending for our souls.

George Woodcock suggested that the last two sentences characterised Orwell as much as his subject.[111]

Orwell wrote a critique of George Bernard Shaw‘s play Arms and the Man. He considered this Shaw’s best play and the most likely to remain socially relevant, because of its theme that war is not, generally speaking, a glorious romantic adventure. His 1945 essay In Defense of P.G. Wodehouse contains an amusing assessment of his writing and also argues that his broadcasts from Germany (during the war) did not really make him a traitor. He accused The Ministry of Information of exaggerating Wodehouse’s actions for propaganda purposes.

Reception and evaluations of Orwell’s works

Arthur Koestler mentioned Orwell’s “uncompromising intellectual honesty [which] made him appear almost inhuman at times.”[112] Ben Wattenberg stated: “Orwell’s writing pierced intellectual hypocrisy wherever he found it.”[113] According to historian Piers Brendon, “Orwell was the saint of common decency who would in earlier days, said his BBC boss Rushbrook Williams, ‘have been either canonised – or burnt at the stake'”.[114] Raymond Williams in Politics and Letters: Interviews with New Left Review describes Orwell as a “successful impersonation of a plain man who bumps into experience in an unmediated way and tells the truth about it.”[115] Christopher Norris declared that Orwell’s “homespun empiricist outlook – his assumption that the truth was just there to be told in a straightforward common-sense way – now seems not merely naïve but culpably self-deluding”.[116] The American scholar Scott Lucas has described Orwell[117] as an enemy of the Left. John Newsinger has argued[118] that Lucas could only do this by portraying “all of Orwell’s attacks on Stalinism [-] as if they were attacks on socialism, despite Orwell’s continued insistence that they were not.”

Orwell’s work has taken a prominent place in the school literature curriculum in England,[119] with Animal Farm a regular examination topic at the end of secondary education (GCSE), and Nineteen Eighty-Four a topic for subsequent examinations below university level (A Levels). Alan Brown noted that this brings to the forefront questions about the political content of teaching practices. Study aids, in particular with potted biographies, might be seen to help propagate the Orwell myth so that as an embodiment of human values he is presented as a “trustworthy guide”, while examination questions sometimes suggest a “right ways of answering” in line with the myth.[120][clarification needed]

Historian John Rodden stated: “John Podhoretz did claim that if Orwell were alive today, he’d be standing with the neo-conservatives and against the Left. And the question arises, to what extent can you even begin to predict the political positions of somebody who’s been dead three decades and more by that time?”[113]

In Orwell’s Victory, Christopher Hitchens argues, “In answer to the accusation of inconsistency Orwell as a writer was forever taking his own temperature. In other words, here was someone who never stopped testing and adjusting his intelligence”.[121]

John Rodden points out the “undeniable conservative features in the Orwell physiognomy” and remarks on how “to some extent Orwell facilitated the kinds of uses and abuses by the Right that his name has been put to. In other ways there has been the politics of selective quotation.”[113] Rodden refers to the essay “Why I Write“, in which Orwell refers to the Spanish Civil War as being his “watershed political experience”, saying “The Spanish War and other events in 1936–37, turned the scale. Thereafter I knew where I stood. Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written directly or indirectly against totalitarianism and for Democratic Socialism as I understand it.” (emphasis in original)[113] Rodden goes on to explain how, during the McCarthy era, the introduction to the Signet edition of Animal Farm, which sold more than 20 million copies, makes use of “the politics of ellipsis”:

If the book itself, Animal Farm, had left any doubt of the matter, Orwell dispelled it in his essay Why I Write: ‘Every line of serious work that I’ve written since 1936 has been written directly or indirectly against Totalitarianism … dot, dot, dot, dot.’ “For Democratic Socialism” is vaporised, just like Winston Smith did it at the Ministry of Truth, and that’s very much what happened at the beginning of the McCarthy era and just continued, Orwell being selectively quoted.[113]

Fyvel wrote about Orwell: “His crucial experience … was his struggle to turn himself into a writer, one which led through long periods of poverty, failure and humiliation, and about which he has written almost nothing directly. The sweat and agony was less in the slum-life than in the effort to turn the experience into literature.”[122][123]

In October 2015 Finlay Publisher, for the Orwell Society, published George Orwell ‘The Complete Poetry’, compiled and presented by Dione Venables.[124]

Influence on language and writing

In his essay “Politics and the English Language” (1946), Orwell wrote about the importance of precise and clear language, arguing that vague writing can be used as a powerful tool of political manipulation because it shapes the way we think. In that essay, Orwell provides six rules for writers:

- Never use a metaphor, simile or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

- Never use a long word where a short one will do.

- If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

- Never use the passive where you can use the active.

- Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

- Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.[125]

Andrew N. Rubin argues, “Orwell claimed that we should be attentive to how the use of language has limited our capacity for critical thought just as we should be equally concerned with the ways in which dominant modes of thinking have reshaped the very language that we use.”[126]

The adjective Orwellian connotes an attitude and a policy of control by propaganda, surveillance, misinformation, denial of truth, and manipulation of the past. In Nineteen Eighty-Four Orwell described a totalitarian government that controlled thought by controlling language, making certain ideas literally unthinkable. Several words and phrases from Nineteen Eighty-Four have entered popular language. Newspeak is a simplified and obfuscatory language designed to make independent thought impossible. Doublethink means holding two contradictory beliefs simultaneously. The Thought Police are those who suppress all dissenting opinion. Prolefeed is homogenised, manufactured superficial literature, film and music, used to control and indoctrinate the populace through docility. Big Brother is a supreme dictator who watches everyone.

Orwell may have been the first to use the term cold war to refer to the state of tension between powers in the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc that followed the Second World War, in his essay, “You and the Atom Bomb”, published in Tribune, 19 October 1945. He wrote:

We may be heading not for general breakdown but for an epoch as horribly stable as the slave empires of antiquity. James Burnham‘s theory has been much discussed, but few people have yet considered its ideological implications – this is, the kind of world-view, the kind of beliefs, and the social structure that would probably prevail in a State which was at once unconquerable and in a permanent state of ‘cold war’ with its neighbours.[127]

Museum

In 2014 it was announced that Orwell’s birthplace, a bungalow in Motihari, Bihar, in India would become the world’s first Orwell museum.[10][128]

Modern Culture

In 2014 a play written by playwright Joe Sutton titled Orwell in America was first performed. It is a fictitious account of Orwell doing a book tour in America (something he never did in his lifetime). It moved to Off-Broadway in 2016.[129]

Personal life

Childhood

Jacintha Buddicom‘s account Eric & Us provides an insight into Blair’s childhood.[130] She quoted his sister Avril that “he was essentially an aloof, undemonstrative person” and said herself of his friendship with the Buddicoms: “I do not think he needed any other friends beyond the schoolfriend he occasionally and appreciatively referred to as ‘CC'”. She could not recall his having schoolfriends to stay and exchange visits as her brother Prosper often did in holidays.[131] Cyril Connolly provides an account of Blair as a child in Enemies of Promise.[23] Years later, Blair mordantly recalled his prep school in the essay “Such, Such Were the Joys“, claiming among other things that he “was made to study like a dog” to earn a scholarship, which he alleged was solely to enhance the school’s prestige with parents. Jacintha Buddicom repudiated Orwell’s schoolboy misery described in the essay, stating that “he was a specially happy child”. She noted that he did not like his name, because it reminded him of a book he greatly disliked – Eric, or, Little by Little, a Victorian boys’ school story.[132]

Connolly remarked of him as a schoolboy, “The remarkable thing about Orwell was that alone among the boys he was an intellectual and not a parrot for he thought for himself”.[23] At Eton, John Vaughan Wilkes, his former headmaster’s son recalled, “… he was extremely argumentative – about anything – and criticising the masters and criticising the other boys … We enjoyed arguing with him. He would generally win the arguments – or think he had anyhow.”[133] Roger Mynors concurs: “Endless arguments about all sorts of things, in which he was one of the great leaders. He was one of those boys who thought for himself …”[134]

Blair liked to carry out practical jokes. Buddicom recalls him swinging from the luggage rack in a railway carriage like an orangutan to frighten a woman passenger out of the compartment.[14] At Eton he played tricks on John Crace, his Master in College, among which was to enter a spoof advertisement in a College magazine implying pederasty.[135] Gow, his tutor, said he “made himself as big a nuisance as he could” and “was a very unattractive boy”.[136] Later Blair was expelled from the crammer at Southwold for sending a dead rat as a birthday present to the town surveyor.[137] In one of his As I Please essays he refers to a protracted joke when he answered an advertisement for a woman who claimed a cure for obesity.[138]

Blair had an interest in natural history which stemmed from his childhood. In letters from school he wrote about caterpillars and butterflies,[139] and Buddicom recalls his keen interest in ornithology. He also enjoyed fishing and shooting rabbits, and conducting experiments as in cooking a hedgehog[14] or shooting down a jackdaw from the Eton roof to dissect it.[134] His zeal for scientific experiments extended to explosives – again Buddicom recalls a cook giving notice because of the noise. Later in Southwold his sister Avril recalled him blowing up the garden. When teaching he enthused his students with his nature-rambles both at Southwold[140] and Hayes.[141] His adult diaries are permeated with his observations on nature.

Relationships and marriage

Buddicom and Blair lost touch shortly after he went to Burma, and she became unsympathetic towards him. She wrote that it was because of the letters he wrote complaining about his life, but an addendum to Eric & Us by Venables reveals that he may have lost her sympathy through an incident which was, at best, a clumsy attempt at seduction.[14]

Mabel Fierz, who later became Blair’s confidante, said: “He used to say the one thing he wished in this world was that he’d been attractive to women. He liked women and had many girlfriends I think in Burma. He had a girl in Southwold and another girl in London. He was rather a womaniser, yet he was afraid he wasn’t attractive.”[142]

Brenda Salkield (Southwold) preferred friendship to any deeper relationship and maintained a correspondence with Blair for many years, particularly as a sounding board for his ideas. She wrote: “He was a great letter writer. Endless letters, and I mean when he wrote you a letter he wrote pages.”[22] His correspondence with Eleanor Jacques (London) was more prosaic, dwelling on a closer relationship and referring to past rendezvous or planning future ones in London and Burnham Beeches.[143]

When Orwell was in the sanatorium in Kent, his wife’s friend Lydia Jackson visited. He invited her for a walk and out of sight “an awkward situation arose.”[144] Jackson was to be the most critical of Orwell’s marriage to Eileen O’Shaughnessy, but their later correspondence hints at a complicity. Eileen at the time was more concerned about Orwell’s closeness to Brenda Salkield. Orwell had an affair with his secretary at Tribune which caused Eileen much distress, and others have been mooted. In a letter to Ann Popham he wrote: “I was sometimes unfaithful to Eileen, and I also treated her badly, and I think she treated me badly, too, at times, but it was a real marriage, in the sense that we had been through awful struggles together and she understood all about my work, etc.”[145]Similarly he suggested to Celia Kirwan that they had both been unfaithful.[146] There are several testaments that it was a well-matched and happy marriage.[147][148][149]

Blair was very lonely after Eileen’s death, and desperate for a wife, both as companion for himself and as mother for Richard. He proposed marriage to four women, including Celia Kirwan, and eventually Sonia Brownell accepted.[150] Orwell had met her when she was assistant to Cyril Connolly, at Horizon literary magazine.[151] They were married on 13 October 1949, only three months before Orwell’s death. Some maintain that Sonia was the model for Julia in Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Religious views

Orwell regularly participated in the social and civic life of the church, and yet was an atheist, both critical of religious doctrine and of religious organisations. He attended Holy Communion at the Church of England regularly,[152] and makes allusions to Anglican rites in his book A Clergyman’s Daughter. He was extremely well-read in Biblical literature and could quote lengthy passages from the Book of Common Prayer from memory.[153] However, his forensic knowledge of the Bible came coupled with unsparing criticism of its philosophy, and as an adult he could not bring himself to believe in its tenets. He said clearly in part V of his essay, “Such, Such Were the Joys“: “Till about the age of fourteen I believed in God, and believed that the accounts given of him were true. But I was well aware that I did not love him.”[154] Of his regular Church attendance, he said: “It seems rather mean to go to HC [Holy Communion] when one doesn’t believe, but I have passed myself off for pious & there is nothing for it but to keep up with the deception.”[155]Despite this, he had two Anglican marriages and left instructions for an Anglican funeral.[156] Orwell directly contrasted Christianity with secular humanism in his essay “Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool“, finding the latter philosophy more palatable and less “self-interested.” Literary critic James Wood wrote that in the struggle, as he saw it, between Christianity and humanism, “Orwell was on the humanist side, of course—basically an unmetaphysical, English version of Camus’s philosophy of perpetual godless struggle.”[157]

Orwell’s writing was often explicitly critical of religion, and Christianity in particular. He found the church to be a “selfish … church of the landed gentry” with its establishment “out of touch” with the majority of its communicants and altogether a pernicious influence on public life.[158] In their 1972 study, The Unknown Orwell, the writers Peter Stansky and William Abrahams noted that at Eton Blair displayed a “sceptical attitude” to Christian belief.[159] Crick observed that Orwell displayed “a pronounced anti-Catholicism”.[160] Evelyn Waugh, writing in 1946, acknowledged Orwell’s high moral sense and respect for justice but believed “he seems never to have been touched at any point by a conception of religious thought and life.”[161] His contradictory and sometimes ambiguous views about the social benefits of religious affiliation mirrored the dichotomies between his public and private lives: Stephen Ingle wrote that it was as if the writer George Orwell “vaunted” his unbelief while Eric Blair the individual retained “a deeply ingrained religiosity”. Ingle later noted that Orwell did not accept the existence of an afterlife, believing in the finality of death while living and advocating a moral code based on Judeo-Christian beliefs.[162][163]

Political views

Orwell liked to provoke arguments by challenging the status quo, but he was also a traditionalist with a love of old English values. He criticised and satirised, from the inside, the various social milieux in which he found himself – provincial town life in A Clergyman’s Daughter; middle-class pretension in Keep the Aspidistra Flying; preparatory schools in “Such, Such Were the Joys”; colonialism in Burmese Days, and some socialist groups in The Road to Wigan Pier. In his Adelphi days he described himself as a “Tory–anarchist.”[164][165]