Mario Vargas Llosa — The War of the End of the World — Videos

Writer Mario Vargas Llosa on the Importance of Literature

Mario Vargas Llosa – Literature, Freedom, and Power

A personal journey: from Marxism to Liberalism by Mario Vargas Llosa

An Evening with Mario Vargas Llosa and John King (The Americas Society).

Mario Vargas Llosa – PRI Perfect Dictatorship – English Subs

Frost Over The World – Mario Vargas Llosa – 28 Sep 07

Mario Vargas Llosa Interview | Part 1 | Skavlan

Mario Vargas Llosa Interview | Part 2 | Skavlan

Mario Vargas Llosa Nobel Prize Literature

Mario Vargas Llosa: sobre el Varón de Caña Brava (“La guerra del fin del mundo”)

Mario Vargas Llosa

| Mario Vargas Llosa | |

|---|---|

|

BornJorge Mario Pedro Vargas Llosa

March 28, 1936

Arequipa, Arequipa, PeruCitizenshipPeru, Spain[1]Alma materNational University of San Marcos

Complutense University of MadridLiterary movementLatin American boomNotable awardsMiguel de Cervantes Prize

1994

Nobel Prize in Literature

2010ChildrenÁlvaro Vargas Llosa

Gonzalo Vargas Llosa

Morgana Vargas Llosa

Signature![]() Websitewww.mvargasllosa.com

Websitewww.mvargasllosa.com

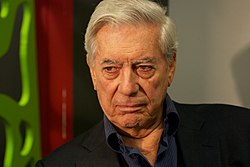

Jorge Mario Pedro Vargas Llosa, 1st Marquis of Vargas Llosa (/ˈvɑrɡəs ˈjoʊsə/;[2]Spanish: [ˈmaɾjo ˈβaɾgas ˈʎosa]; born March 28, 1936) is a Peruvian writer, politician, journalist, essayist, college professor, and recipient of the 2010 Nobel Prize in Literature.[3] Vargas Llosa is one of Latin America’s most significant novelists and essayists, and one of the leading writers of his generation. Some critics consider him to have had a larger international impact and worldwide audience than any other writer of theLatin American Boom.[4] Upon announcing the 2010 Nobel Prize in Literature, the Swedish Academy said it had been given to Vargas Llosa “for his cartography of structures of power and his trenchant images of the individual’s resistance, revolt, and defeat”.[5]

Vargas Llosa rose to fame in the 1960s with novels such as The Time of the Hero (La ciudad y los perros, literally The City and the Dogs, 1963/1966[6]), The Green House (La casa verde, 1965/1968), and the monumental Conversation in the Cathedral (Conversación en la catedral, 1969/1975). He writes prolifically across an array ofliterary genres, including literary criticism and journalism. His novels include comedies, murder mysteries, historical novels, and political thrillers. Several, such as Captain Pantoja and the Special Service (1973/1978) and Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter (1977/1982), have been adapted as feature films.

Many of Vargas Llosa’s works are influenced by the writer’s perception of Peruvian society and his own experiences as a native Peruvian. Increasingly, however, he has expanded his range, and tackled themes that arise from other parts of the world. In his essays, Vargas Llosa has made many criticisms of nationalism in different parts of the world.[7] Another change over the course of his career has been a shift from a style and approach associated with literary modernism, to a sometimes playfulpostmodernism.

Like many Latin American writers, Vargas Llosa has been politically active throughout his career; over the course of his life, he has gradually moved from the political lefttowards liberalism or neoliberalism. While he initially supported the Cuban revolutionary government of Fidel Castro, Vargas Llosa later became disenchanted with his policies. He ran for the Peruvian presidency in 1990 with the center-right Frente Democrático coalition, advocating neoliberal reforms, but lost the election to Alberto Fujimori. He is the person who, in 1990, “coined the phrase that circled the globe”,[8] declaring on Mexican television, “Mexico is the perfect dictatorship”, a statement which became an adage during the following decade.

Early life and family

Mario Vargas Llosa was born to a middle-class family[9] on March 28, 1936, in the Peruvian provincial city of Arequipa.[10] He was the only child of Ernesto Vargas Maldonado and Dora Llosa Ureta (the former a radio operator in an aviation company, the latter the daughter of an old criollo family), who separated a few months before his birth.[10] Shortly after Mario’s birth, his father revealed that he was having an affair with a German woman; consequently, Mario has two younger half-brothers: Enrique and Ernesto Vargas.[11]

Mario Vargas Llosa’s thesis«Bases para una interpretación de Rubén Darío», presented to his alma mater, the National University of San Marcos (Peru), in 1958.

Vargas Llosa lived with his maternal family in Arequipa until a year after his parents’ divorce, when his maternal grandfather was named honorary consul for Peru in Bolivia.[10] With his mother and her family, Vargas Llosa then moved to Cochabamba, Bolivia, where he spent the early years of his childhood.[10] His maternal family, the Llosas, were sustained by his grandfather, who managed a cotton farm.[12] As a child, Vargas Llosa was led to believe that his father had died—his mother and her family did not want to explain that his parents had separated.[13] During the government of Peruvian President José Bustamante y Rivero, Vargas Llosa’s maternal grandfather obtained a diplomatic post in the Peruvian coastal city of Piura and the entire family returned to Peru.[13] While in Piura, Vargas Llosa attended elementary school at the religious academy Colegio Salesiano.[14] In 1946, at the age of ten, he moved to Lima and met his father for the first time.[14] His parents re-established their relationship and lived in Magdalena del Mar, a middle-class Lima suburb, during his teenage years.[15] While in Lima, he studied at the Colegio La Salle, a Christian middle school, from 1947 to 1949.[16]

When Vargas Llosa was fourteen, his father sent him to the Leoncio Prado Military Academy in Lima.[17] At the age of 16, before his graduation, Vargas Llosa began working as an amateur journalist for local newspapers.[18] He withdrew from the military academy and finished his studies in Piura, where he worked for the local newspaper, La Industria, and witnessed the theatrical performance of his first dramatic work, La huida del Inca.[19]

In 1953, during the government of Manuel A. Odría, Vargas Llosa enrolled in Lima’s National University of San Marcos, to study law and literature.[20] He married Julia Urquidi, his maternal uncle’s sister-in-law, in 1955 at the age of 19; she was 10 years older.[18] Vargas Llosa began his literary career in earnest in 1957 with the publication of his first short stories, “The Leaders” (“Los jefes”) and “The Grandfather” (“El abuelo”), while working for two Peruvian newspapers.[21] Upon his graduation from the National University of San Marcos in 1958, he received a scholarship to study at the Complutense University of Madrid in Spain.[22] In 1960, after his scholarship in Madrid had expired, Vargas Llosa moved to France under the impression that he would receive a scholarship to study there; however, upon arriving in Paris, he learned that his scholarship request was denied.[23] Despite Mario and Julia’s unexpected financial status, the couple decided to remain in Paris where he began to write prolifically.[23] Their marriage lasted only a few more years, ending in divorce in 1964.[24] A year later, Vargas Llosa married his first cousin, Patricia Llosa,[24] with whom he had three children: Álvaro Vargas Llosa (born 1966), a writer and editor; Gonzalo (born 1967), a businessman; and Morgana (born 1974), a photographer.

Writing career

Beginning and first major works

Vargas Llosa’s first novel, The Time of the Hero (La ciudad y los perros), was published in 1963. The book is set among a community of cadets in a Lima military school, and the plot is based on the author’s own experiences at Lima’s Leoncio Prado Military Academy.[25] This early piece gained wide public attention and immediate success.[26] Its vitality and adept use of sophisticated literary techniques immediately impressed critics,[27] and it won the Premio de la Crítica Española award.[26] Nevertheless, its sharp criticism of the Peruvian military establishment led to controversy in Peru. Several Peruvian generals attacked the novel, claiming that it was the work of a “degenerate mind” and stating that Vargas Llosa was “paid by Ecuador” to undermine the prestige of the Peruvian Army.[26]

In 1965, Vargas Llosa published his second novel, The Green House (La casa verde), about a brothel called “The Green House” and how its quasi-mythical presence affects the lives of the characters. The main plot follows Bonifacia, a girl who is about to receive the vows of the church, and her transformation into la Selvatica, the best-known prostitute of “The Green House”. The novel was immediately acclaimed, confirming Vargas Llosa as an important voice of Latin American narrative.[28]The Green House won the first edition of the Rómulo Gallegos International Novel Prize in 1967, contending with works by veteran Uruguayanwriter Juan Carlos Onetti and by Gabriel García Márquez.[29] This novel alone accumulated enough awards to place the author among the leading figures of the Latin American Boom.[30] Some critics still considerThe Green House to be Vargas Llosa’s finest and most important achievement.[30] Indeed, Latin American literary critic Gerald Martin suggests that The Green House is “one of the greatest novels to have emerged from Latin America”.[30]

Vargas Llosa’s third novel, Conversation in the Cathedral (Conversación en la catedral), was published in 1969, when he was 33. This ambitious narrative is the story of Santiago Zavala, the son of a government minister, and Ambrosio, his chauffeur.[31] A random meeting at a dog pound leads the pair to a riveting conversation at a nearby bar known as “The Cathedral”.[32] During the encounter, Zavala searches for the truth about his father’s role in the murder of a notorious Peruvian underworld figure, shedding light on the workings of a dictatorship along the way. Unfortunately for Zavala, his quest results in a dead end with no answers and no sign of a better future.[33] The novel attacks the dictatorial government of Odría by showing how a dictatorship controls and destroys lives.[26] The persistent theme of hopelessness makes Conversation in the Cathedral Vargas Llosa’s most bitter novel.[33]

He lectured Spanish American Literature at King’s College London from 1969 to 1970.[34]

1970s and the “discovery of humor”

In 1971, Vargas Llosa published García Márquez: Story of a Deicide (García Márquez: historia de un deicidio), which was his doctoral thesis for the Complutense University of Madrid.[35][36] Although Vargas Llosa wrote this book-length study about his then friend, the Colombian Nobel laureate writer Gabriel García Márquez, they did not speak to each other again. In 1976, Vargas Llosa punched García Márquez in the face inMexico City at the Palacio de Bellas Artes, ending the friendship.[37] Neither writer had publicly stated the underlying reasons for the quarrel.[38] A photograph of García Márquez sporting a black eye was published in 2007, reigniting public interest in the feud.[39] Despite the decades of silence, in 2007, Vargas Llosa agreed to allow part of his book to be used as the introduction to a 40th-anniversary edition of García Márquez’sOne Hundred Years of Solitude, which was re-released in Spain and throughout Latin America that year.[40]Historia de un Deicidio was also reissued in that year, as part of Vargas Llosa’s complete works.

Following the monumental work Conversation in the Cathedral, Vargas Llosa’s output shifted away from more serious themes such as politics and problems with society. Latin American literary scholar Raymond L. Williams describes this phase in his writing career as “the discovery of humor”.[41] His first attempt at a satirical novel was Captain Pantoja and the Special Service (Pantaleón y las visitadoras), published in 1973.[42]This short, comic novel offers vignettes of dialogues and documents about the Peruvian armed forces and a corps of prostitutes assigned to visit military outposts in remote jungle areas.[43] These plot elements are similar to Vargas Llosa’s earlier novel The Green House, but in a different form. As such, Captain Pantoja and the Special Service is essentially a parody of both The Green House and the literary approach that novel represents.[43] Vargas Llosa’s motivation to write the novel came from actually witnessing prostitutes being hired by the Peruvian Army and brought to serve soldiers in the jungle.[44]

From 1974 to 1987, Vargas Llosa focused on his writing, but also took the time to pursue other endeavors.[45] In 1975, he co-directed an unsuccessful motion-picture adaptation of his novel, Captain Pantoja and the Secret Service.[45] In 1976 he was elected President of PEN International, the worldwide association of writers and oldest human rights organisation, a position he held until 1979.[45] During this time, Vargas Llosa constantly traveled to speak at conferences organized by internationally renowned institutions, such as the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the University of Cambridge, where he was Simón Bolívar Professor and an Overseas Fellow of Churchill College in 1977–78.[46][47][48]

In 1977, Vargas Llosa was elected as a member of the Peruvian Academy of Language, a membership he still holds today. That year, he also published Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter (La tía Julia y el escribidor), based in part on his marriage to his first wife, Julia Urquidi, to whom he dedicated the novel.[49] She later wrote a memoir, Lo que Varguitas no dijo (What Little Vargas Didn’t Say), in which she gives her personal account of their relationship. She states that Vargas Llosa’s account exaggerates many negative points in their courtship and marriage while minimizing her role of assisting his literary career.[50]Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter is considered one of the most striking examples of how the language and imagery of popular culture can be used in literature.[51] The novel was adapted in 1990 into a Hollywood feature film, Tune in Tomorrow.

Later novels

Vargas Llosa’s fourth major novel, The War of the End of the World (La guerra del fin del mundo), was published in 1981 and was his first attempt at a historical novel.[52] This work initiated a radical change in Vargas Llosa’s style towards themes such as messianism and irrational human behaviour.[53] It recreates the War of Canudos, an incident in 19th-century Brazil in which an armed millenarian cult held off a siege by the national army for months.[54] As in Vargas Llosa’s earliest work, this novel carries a sober and serious theme, and its tone is dark.[54] Vargas Llosa’s bold exploration of humanity’s propensity to idealize violence, and his account of a man-made catastrophe brought on by fanaticism on all sides, earned the novel substantial recognition.[55] Because of the book’s ambition and execution, critics have argued that this is one of Vargas Llosa’s greatest literary pieces.[55] Even though the novel has been acclaimed in Brazil, it was initially poorly received because a foreigner was writing about a Brazilian theme.[56] The book was also criticized as revolutionary and anti-socialist.[57] Vargas Llosa says that this book is his favorite and was his most difficult accomplishment.[57]

After completing The War of the End of the World, Vargas Llosa began to write novels that were significantly shorter than many of his earlier books. In 1983, he finished The Real Life of Alejandro Mayta (Historia de Mayta, 1984).[52] The novel focuses on a leftist insurrection that took place on May 29, 1962 in the Andean city of Jauja.[52] Later the same year, during the Sendero Luminoso uprising, Vargas Llosa was asked by the Peruvian President Fernando Belaúnde Terry to join the Investigatory Commission, a task force to inquire into the massacre of eight journalists at the hands of the villagers of Uchuraccay.[58] The Commission’s main purpose was to investigate the murders in order to provide information regarding the incident to the public.[59] Following his involvement with the Investigatory Commission, Vargas Llosa published a series of articles to defend his position in the affair.[59] In 1986, he completed his next novel, Who Killed Palomino Molero (¿Quién mató a Palomino Molero?), which he began writing shortly after the end of the Uchuraccay investigation.[59] Though the plot of this mystery novel is similar to the tragic events at Uchuraccay, literary critic Roy Boland points out that it was not an attempt to reconstruct the murders, but rather a “literary exorcism” of Vargas Llosa’s own experiences during the commission.[60] The experience also inspired one of Vargas Llosa’s later novels, Death in the Andes (Lituma en los Andes), originally published in 1993 in Barcelona.[61]

It would be almost 20 years before Vargas Llosa wrote another major work: The Feast of the Goat (La fiesta del chivo), a political thriller, was published in 2000 (and in English in 2001). According to Williams, it is Vargas Llosa’s most complete and most ambitious novel since The War of the End of the World.[62] Critic Sabine Koellmann sees it in the line of his earlier novels such as “Conversación en la catedral” depicting the effects of authoritarianism, violence and the abuse of power on the individual.[63] Based on the dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo, who governed the Dominican Republic from 1930 until his assassination in 1961, the novel has three main strands: one concerns Urania Cabral, the daughter of a former politician and Trujillo loyalist, who returns for the first time since leaving the Dominican Republic after Trujillo’s assassination 30 years earlier; the second concentrates on the assassination itself, the conspirators who carry it out, and its consequences; and the third and final strand deals with Trujillo himself in scenes from the end of his regime.[62] The book quickly received positive reviews in Spain and Latin America,[64] and has had a significant impact in Latin America, being regarded as one of Vargas Llosa’s best works.[62]

In 2003 he wrote The Way to Paradise where he studies Flora Tristan and Paul Gauguin.

In 2006, Vargas Llosa wrote The Bad Girl (Travesuras de la niña mala), which journalist Kathryn Harrison argues is a rewrite (rather than simply a recycling) of Gustave Flaubert‘s Madame Bovary (1856).[65] In Vargas Llosa’s version, the plot relates the decades-long obsession of its narrator, a Peruvian expatriate in Paris, with a woman with whom he first fell in love when both were teenagers.

Later life and political involvement

Like many other Latin American intellectuals, Vargas Llosa was initially a supporter of the Cuban revolutionary government of Fidel Castro.[28] He studied Marxism in depth as a university student and was later persuaded by communist ideals after the success of the Cuban Revolution.[66] Gradually, Vargas Llosa came to believe that Cuban socialism was incompatible with what he considered to be general liberties and freedoms.[67] The official rupture between the writer and the policies of the Cuban government occurred with the so-called ‘Padilla Affair’, when the Castro regime imprisoned the poet Heberto Padilla for a month in 1971.[68] Vargas Llosa, along with other intellectuals of the time, wrote to Castro protesting the Cuban political system and its imprisonment of the artist.[69] Vargas Llosa has identified himself with liberalism rather than extreme left-wing political ideologies ever since.[70] Since he relinquished his earlier leftism, he has opposed both left- and right-wing authoritarian regimes.[71]

With his appointment to the Investigatory Commission on the Uchuraccay massacre in 1983, he experienced what literary critic Jean Franco calls “the most uncomfortable event in [his] political career”.[61]Unfortunately for Vargas Llosa, his involvement with the Investigatory Commission led to immediate negative reactions and defamation from the Peruvian press; many suggested that the massacre was a conspiracy to keep the journalists from reporting the presence of government paramilitary forces in Uchuraccay.[59] The commission concluded that it was the indigenous villagers who had been responsible for the killings; for Vargas Llosa the incident showed “how vulnerable democracy is in Latin America and how easily it dies under dictatorships of the right and left”.[72] These conclusions, and Vargas Llosa personally, came under intense criticism: anthropologist Enrique Mayer, for instance, accused him of “paternalism”,[73] while fellow anthropologist Carlos Iván Degregori criticized him for his ignorance of the Andean world.[74] Vargas Llosa was accused of actively colluding in a government cover-up of army involvement in the massacre.[59] US Latin American literature scholar Misha Kokotovic summarizes that the novelist was charged with seeing “indigenous cultures as a ‘primitive’ obstacle to the full realization of his Western model of modernity”.[75] Shocked both by the atrocity itself and then by the reaction his report had provoked, Vargas Llosa responded that his critics were apparently more concerned with his report than with the hundreds of peasants who would later die at the hands of the Sendero Luminoso guerrilla organization.[76]

Vargas Llosa at the founding act ofUPD, September 2007

Over the course of the decade, Vargas Llosa became known as a “neoliberal“, although he personally dislikes the term and considers it “pure nonsense” and only used for derision.[77] In 1987, he helped form and soon became a leader of the Movimiento Libertad.[78] The following year his party entered a coalition with the parties of Peru’s two principal conservative politicians at the time, ex-president Fernando Belaúnde Terry (of the Popular Action party) and Luis Bedoya Reyes (of the Partido Popular Cristiano), to form the tripartite center-right coalition known as Frente Democrático (FREDEMO).[78] He ran for the presidency of Peru in 1990 as the candidate of the FREDEMO coalition. He proposed a drastic economic austerity program that frightened most of the country’s poor; this program emphasized the need for privatization, a market economy, free trade, and most importantly, the dissemination of private property.[79] Although he won the first round with 34% of the vote, Vargas Llosa was defeated by a then-unknown agricultural engineer, Alberto Fujimori, in the subsequent run-off.[79] Vargas Llosa included an account of his run for the presidency in the memoir A Fish in the Water (El pez en el agua, 1993).[80] Since his political defeat, he has focused mainly on his writing, with only occasional political involvement.[81]

A month after losing the election, at the invitation of Octavio Paz, Vargas Llosa attended a conference in Mexico entitled, “The 20th Century: The Experience of Freedom”. Focused on the collapse of communist rule in central and eastern Europe, it was broadcast on Mexican television from 27 August to 2 September. Addressing the conference on 30 August 1990, Vargas Llosa embarrassed his hosts by condemning the Mexican system of power based on the rule of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), which had been in power for 61 years. Criticizing the PRI by name, he commented, “I don’t believe that there has been in Latin America any case of a system of dictatorship which has so efficiently recruited the intellectual milieu, bribing it with great subtlety.” He declared, “Mexico is the perfect dictatorship. The perfect dictatorship is not communism, not the USSR, not Fidel Castro; the perfect dictatorship is Mexico. Because it is a camouflaged dictatorship.”[82][8] The statement, “Mexico is the perfect dictatorship” became a cliché in Mexico[83] and internationally, until the PRI fell from power in 2000.

Vargas Llosa has mainly lived in Madrid since the 1990s,[84] but spends roughly three months of the year in Peru with his extended family.[79] He also frequently visits London where he occasionally spends long periods. Vargas Llosa acquired Spanish citizenship in 1993, though he still holds Peruvian nationality. The writer often reiterates his love for both countries. In his Nobel speech he observed: “I carry Peru deep inside me because that is where I was born, grew up, was formed, and lived those experiences of childhood and youth that shaped my personality and forged my calling”. He then added: “I love Spain as much as Peru, and my debt to her is as great as my gratitude. If not for Spain, I never would have reached this podium or become a known writer”.[85]

In 1994 he was elected a member of the Real Academia Española (Royal Spanish Academy)[86] and has been involved in the country’s political arena. In February 2008 he stopped supporting the People’s Party in favor of the recently created Union, Progress and Democracy, claiming that certain conservative views held by the former party are at odds with his classical liberal beliefs. His political ideologies appear in the bookPolítica razonable, written with Fernando Savater, Rosa Díez, Álvaro Pombo, Albert Boadella and Carlos Martínez Gorriarán.[87] He continues to write, both journalism and fiction, and to travel extensively. He has also taught as a visiting professor at a number of prominent universities.[88]

On November 18, 2010, Vargas Llosa received the honorary degree Degree of Letters from the City College of New York of the City University of New York, where he also delivered the President’s Lecture.[89]

On 4 February 2011, Vargas Llosa was raised into the Spanish nobility by King Juan Carlos I with the hereditary title of Marqués de Vargas Llosa (English: Marquis of Vargas Llosa).[90][91]

In April 2011, the writer took part in the Peruvian general election, 2011 by saying he was going to vote for Alejandro Toledo (Peruvian former president 2001–2006). After casting his vote, he said his country should stay in the path of legality and freedom.[92][93]

As for hobbies, Vargas Llosa is very fond of association football, and is a renowned supporter of Universitario de Deportes.[94] The writer himself has confessed in his book A Fish in the Water since childhood he has been a fan of the ‘cream colored’ team from Peru, which was first seen in the field one day in 1946 when he was only 10 years old.[95] In February 2011, Vargas Llosa was awarded with an honorary life membership of this football club, in a ceremony which took place in the Monumental Stadium of Lima.[96][97]

Style of writing

Plot, setting, and major themes

Vargas Llosa’s style encompasses historical material as well as his own personal experiences.[98] For example, in his first novel, The Time of the Hero, his own experiences at the Leoncio Prado military school informed his depiction of the corrupt social institution which mocked the moral standards it was supposed to uphold.[25] Furthermore, the corruption of the book’s school is a reflection of the corruption of Peruvian society at the time the novel was written.[27] Vargas Llosa frequently uses his writing to challenge the inadequacies of society, such as demoralization and oppression by those in political power towards those who challenge this power. One of the main themes he has explored in his writing is the individual’s struggle for freedom within an oppressive reality.[99] For example, his two-volume novel Conversation in the Cathedral is based on the tyrannical dictatorship of Peruvian President Manuel A. Odría.[100] The protagonist, Santiago, rebels against the suffocating dictatorship by participating in the subversive activities of leftist political groups.[101] In addition to themes such as corruption and oppression, Vargas Llosa’s second novel, The Green House, explores “a denunciation of Peru’s basic institutions”, dealing with issues of abuse and exploitation of the workers in the brothel by corrupt military officers.[41]

Many of Vargas Llosa’s earlier novels were set in Peru, while in more recent work he has expanded to other regions of Latin America, such as Brazil and the Dominican Republic.[102] His responsibilities as a writer and lecturer have allowed him to travel frequently and led to settings for his novels in regions outside of Peru.[45]The War of the End of the World was his first major work set outside Peru.[26] Though the plot deals with historical events of the Canudos revolt against the Brazilian government, the novel is not based directly on historical fact; rather, its main inspiration is the non-fiction account of those events published by Brazilian writer Euclides da Cunha in 1902.[54]The Feast of the Goat, based on the dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo, takes place in the Dominican Republic;[62] in preparation for this novel, Vargas Llosa undertook a comprehensive study of Dominican history.[103] The novel was characteristically realist, and Vargas Llosa underscores that he “respected the basic facts, [. . .] I have not exaggerated”, but at the same time he points out “It’s a novel, not a history book, so I took many, many liberties.”[104]

One of Vargas Llosa’s more recent novels, The Way to Paradise (El paraíso en la otra esquina), is set largely in France and Tahiti.[105] Based on the biography of former social reformer Flora Tristan, it demonstrates how Flora and Paul Gauguin were unable to find paradise, but were still able to inspire followers to keep working towards a socialist utopia.[106] Unfortunately, Vargas Llosa was not as successful in transforming these historical figures into fiction. Some critics, such as Barbara Mujica, argue that The Way to Paradise lacks the “audacity, energy, political vision, and narrative genius” that was present in his previous works.[107]

Modernism and postmodernism

The works of Mario Vargas Llosa are viewed as both modernist and postmodernist novels.[108] Though there is still much debate over the differences between modernist and postmodernist literature, literary scholar M. Keith Booker claims that the difficulty and technical complexity of Vargas Llosa’s early works, such as The Green House and Conversation in the Cathedral, are clearly elements of the modern novel.[30]Furthermore, these earlier novels all carry a certain seriousness of attitude—another important defining aspect of modernist art.[108] By contrast, his later novels such as Captain Pantoja and the Special Service, Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter, The Real Life of Alejandro Mayta, and The Storyteller (El hablador) appear to follow a postmodernist mode of writing.[109] These novels have a much lighter, farcical, and comic tone, characteristics of postmodernism.[43] Comparing two of Vargas Llosa’s novels, The Green House and Captain Pantoja and the Special Service, Booker discusses the contrast between modernism and postmodernism found in the writer’s works: while both novels explore the theme of prostitution as well as the workings of the Peruvian military, Booker points out that the former is gravely serious whereas the latter is ridiculously comic.[43]

Mario Vargas Llosa, actor in his play “Los cuentos de la peste”, withAitana Sánchez-Gijón, Teatro Español, Madrid (2015).

Interlacing dialogues

Literary scholar M. Keith Booker argues that Vargas Llosa perfects the technique of interlacing dialogues in his novel The Green House.[43] By combining two conversations that occur at different times, he creates the illusion of a flashback. Vargas Llosa also sometimes uses this technique as a means of shifting location by weaving together two concurrent conversations happening in different places.[110] This technique is a staple of his repertoire, which he began using near the end of his first novel, The Time of the Hero.[111] However, he does not use interlacing dialogues in the same way in all of his novels. For example, in The Green House the technique is used in a serious fashion to achieve a sober tone and to focus on the interrelatedness of important events separated in time or space.[112] In contrast, Captain Pantoja and the Special Service employs this strategy for comic effects and uses simpler spatial shifts.[113] This device is similar to both Virginia Woolf‘s mixing of different characters’ soliloquies and Gustave Flaubert’s counterpoint technique in which he blends together conversation with other events, such as speeches.[110]

Literary influences

Vargas Llosa’s first literary influences were relatively obscure Peruvian writers such as Martín Adán, Carlos Oquendo de Amat, and César Moro.[114] As a young writer, he looked to these revolutionary novelists in search of new narrative structures and techniques in order to delineate a more contemporary, multifaceted experience of urban Peru. He was looking for a style different from the traditional descriptions of land and rural life made famous by Peru’s foremost novelist at the time, José María Arguedas.[115] Vargas Llosa wrote of Arguedas’s work that it was “an example of old-fashioned regionalism that had already exhausted its imaginary possibilities”.[114] Although he did not share Arguedas’s passion for indigenous reality, Vargas Llosa admired and respected the novelist for his contributions to Peruvian literature.[116] Indeed, he has published a book-length study on his work, La utopía arcaica (1996).

Rather than restrict himself to Peruvian literature, Vargas Llosa also looked abroad for literary inspiration. Two French figures, existentialistJean-Paul Sartre and novelist Gustave Flaubert, influenced both his technique and style.[117] Sartre’s influence is most prevalent in Vargas Llosa’s extensive use of conversation.[118] The epigraph of The Time of the Hero, his first novel, is also taken directly from Sartre’s work.[119]Flaubert’s artistic independence—his novels’ disregard of reality and morals—has always been admired by Vargas Llosa,[120] who wrote a book-length study of Flaubert’s aesthetics, The Perpetual Orgy.[121] In his analysis of Flaubert, Vargas Llosa questions the revolutionary power of literature in a political setting; this is in contrast to his earlier view that “literature is an act of rebellion”, thus marking a transition in Vargas Llosa’s aesthetic beliefs.[122] Other critics such as Sabine Köllmann argue that his belief in the transforming power of literature is one of the great continuities that characterize his fictional and non-fictional work, and link his early statement that ‘Literature is Fire’ with his Nobel Prize Speech ‘In Praise of Reading and Writing’.[123]

One of Vargas Llosa’s favourite novelists, and arguably the most influential on his writing career, is the American William Faulkner.[124] Vargas Llosa considers Faulkner “the writer who perfected the methods of the modern novel”.[125] Both writers’ styles include intricate changes in time and narration.[118][125] In The Time of the Hero, for example, aspects of Vargas Llosa’s plot, his main character’s development and his use of narrative time are influenced by his favourite Faulkner novel, Light in August.[126]

In addition to the studies of Arguedas and Flaubert, Vargas Llosa has written literary criticisms of other authors that he has admired, such as Gabriel García Márquez, Albert Camus, Ernest Hemingway, and Jean-Paul Sartre.[127] The main goals of his non-fiction works are to acknowledge the influence of these authors on his writing, and to recognize a connection between himself and the other writers;[127] critic Sara Castro-Klarén argues that he offers little systematic analysis of these authors’ literary techniques.[127] In The Perpetual Orgy, for example, he discusses the relationship between his own aesthetics and Flaubert’s, rather than focusing on Flaubert’s alone.[128]

Impact

Mario Vargas Llosa is considered a major Latin American writer, alongside other authors such as Octavio Paz, Julio Cortázar, Jorge Luis Borges, Gabriel García Márquez and Carlos Fuentes.[129] In his book The New Novel in Latin America (La Nueva Novela), Fuentes offers an in-depth literary criticism of the positive influence Vargas Llosa’s work has had on Latin American literature.[130] Indeed, for the literary critic Gerald Martin, writing in 1987, Vargas Llosa was “perhaps the most successful [. . . and] certainly the most controversial Latin American novelist of the past twenty-five years”.[131]

Most of Vargas Llosa’s narratives have been translated into multiple languages, marking his international critical success.[129] Vargas Llosa is also noted for his substantial contribution to journalism, an accomplishment characteristic of few other Latin American writers.[132] He is recognized among those who have most consciously promoted literature in general, and more specifically the novel itself, as avenues for meaningful commentary about life.[133] During his career, he has written more than a dozen novels and many other books and stories, and, for decades, he has been a voice for Latin American literature.[134] He has won numerous awards for his writing, from the 1959 Premio Leopoldo Alas and the 1962 Premio Biblioteca Breve to the 1993 Premio Planeta (for Death in the Andes) and the Jerusalem Prize in 1995.[135] The literary critic Harold Bloom has included his novel The War of the End of the World in his list of essential literary works in the Western Canon. An important distinction he has received is the 1994 Miguel de Cervantes Prize, considered the most important accolade in Spanish-language literature and awarded to authors whose “work has contributed to enrich, in a notable way, the literary patrimony of the Spanish language”.[136] In 2002, Vargas was the recipient of the PEN/Nabokov Award. Vargas Llosa also received the 2005 Irving Kristol Award from the American Enterprise Institute and was the 2008 recipient of the Harold and Ethel L. Stellfox Visiting Scholar and Writers Award at Dickinson College.[137]

A number of Vargas Llosa’s works have been adapted for the screen, including The Time of the Hero and Captain Pantoja and the Special Service (both by the Peruvian director Francisco Lombardi) and The Feast of the Goat (by Vargas Llosa’s cousin, Luis Llosa).[138]Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter was turned into the English-language film, Tune in Tomorrow. The Feast of the Goat has also been adapted as a theatrical play by Jorge Alí Triana, a Colombian playwright and director.[139]

Awards and honors

-

This list is incomplete; you can help by expanding it.

- 1967 – Rómulo Gallegos Prize

- 1986 – Grinzane Cavour Prize for Fiction foreign

- 1986 – Prince of Asturias Award for Literature

- 1993 – Planeta Prize for Death in the Andes, a thriller starring one of the characters in Who Killed Palomino Molero?

- 1994 – Miguel de Cervantes Prize, after taking Spanish citizenship

- 1996 – Peace Prize of the German Book Trade

- 1999 – Menéndez Pelayo International Prize

- 2004 – Independent Foreign Fiction Prize

- 2004 – Grinzane Cavour Prize

- 2006 – Maria Moors Cabot prize

- 2010 – Nobel Prize for Literature

- 2010 – International Award Viareggio-Versilia

- 2012 – “10 Most Influential Ibero American Intellectuals” of the year – Foreign Policy magazine [1]

- 2012 Carlos Fuentes International Prize for Literary Creation in the Spanish Language[140]

- Grand Cross with Diamonds of the Order of the Sun (Peru)

- Austrian Cross of Honour for Science and Art, 1st class

- Chevalier of the Legion of Honour (France)

- Officer of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (France)

- Commander of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (France)

- Commander of the Order of the Aztec Eagle (Mexico)

- Grand Cross with Silver Star of the Order of Ruben Dario (Nicaragua)

- Grand Cross with Silver Star of the Order of Christopher Columbus (Dominican Republic)

Selected works

Fiction

- 1959 – Los jefes (The Cubs and Other Stories, 1979)

- 1963 – La ciudad y los perros (The Time of the Hero, 1966)

- 1966 – La casa verde (The Green House, 1968)

- 1969 – Conversación en la catedral (Conversation in the Cathedral, 1975)

- 1973 – Pantaleón y las visitadoras (Captain Pantoja and the Special Service, 1978)

- 1977 – La tía Julia y el escribidor (Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter, 1982)

- 1981 – La guerra del fin del mundo (The War of the End of the World, 1984)

- 1984 – Historia de Mayta (The Real Life of Alejandro Mayta, 1985)

- 1986 – ¿Quién mató a Palomino Molero? (Who Killed Palomino Molero?, 1987)

- 1987 – El hablador (The Storyteller, 1989)

- 1988 – Elogio de la madrastra (In Praise of the Stepmother, 1990)

- 1993 – Lituma en los Andes (Death in the Andes, 1996)

- 1997 – Los cuadernos de don Rigoberto (The Notebooks of Don Rigoberto, 1998)

- 2000 – La fiesta del chivo (The Feast of the Goat, 2001)

- 2003 – El paraíso en la otra esquina (The Way to Paradise, 2003)

- 2006 – Travesuras de la niña mala (The Bad Girl, 2007)

- 2010 – El sueño del celta (The Dream of the Celt, 2010)

- 2013 – El héroe discreto (The Discreet Hero, 2015)

Non-fiction

- 1958 – Bases para una interpretación de Rubén Darío (The basis for interpretation of Ruben Dario)

- 1971 – García Márquez: historia de un deicidio (García Márquez: Story of a Deicide)

- 1975 – La orgía perpetua: Flaubert y “Madame Bovary” (The Perpetual Orgy)

- 1990 – La verdad de las mentiras: ensayos sobre la novela moderna (A Writer’s Reality)

- 1993 – El pez en el agua. Memorias (A Fish in the Water)

- 1996 – La utopía arcaica: José María Arguedas y las ficciones del indigenismo (Archaic utopia: José María Arguedas and the fictions of indigenismo)

- 1997 – Cartas a un joven novelista (Letters to a Young Novelist)

- 2000 – Nationalismus als neue Bedrohung (Nationalism as a new threat)[7]

- 2001 – El lenguaje de la pasión (The Language of Passion)

- 2004 – La tentación de lo imposible (The Temptation of the Impossible)

- 2007 – El Pregón de Sevilla (as Introduction for LOS TOROS)

- 2009 – El viaje a la ficción: El mundo de Juan Carlos Onetti

- 2011 – Touchstones: Essays on Literature, Art, and Politics

- 2012 – La civilización del espectáculo

- 2012 – In Praise of Reading and Fiction: The Nobel Lecture

- 2014 – Mi trayectora intelectual (My Intellectual Journey)

- 2015 – Notes on the Death of Culture

Drama

- 1952 – La huida del inca

- 1981 – La señorita de Tacna

- 1983 – Kathie y el hipopótamo

- 1986 – La Chunga

- 1993 – El loco de los balcones

- 1996 – Ojos bonitos, cuadros feos

- 2007 – Odiseo y Penélope

- 2008 – Al pie del Támesis

- 2010 – Las mil y una noches

Vargas Llosa’s essays and journalism have been collected as Contra viento y marea, issued in three volumes (1983, 1986, and 1990). A selection has been edited by John King and translated and published asMaking Waves. 2003 – “The Language of Passion”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mario_Vargas_Llosa

The War of the End of the World

| This article does not cite any references or sources. (February 2008) |

The War of the End of the World (Spanish: La guerra del fin del mundo) is a 1981novel written by Peruvian novelist Mario Vargas Llosa. It is a novelization of the War of Canudosconflict in late 19th-century Brazil.

Plot summary

In the midst of the economic decline — following drought and the end of slavery — in the province of Bahia in Northeastern Brazil, the poor of the backlands are attracted by the charismatic figure and simple religious teachings of Antonio Conselheiro, the Counselor, who preaches that the end of the world is imminent and that the political chaos that surrounds the collapse of the Empire of Brazil and its replacement by a republic is the work of the devil.

Seizing a fazenda in an area blighted by economic decline at Canudos the Counselor’s followers build a large town and defeat repeated and ever larger military expeditions designed to remove them. As the state’s violence against them increases they too turn increasingly violent, even seizing the modern weapons deployed against them. In an epic final clash a whole army is sent to extirpate Canudos and instigates a terrible and brutal battle with the poor while politicians of the old order see their world destroyed in the conflagration.

Analysis

It is generally believed that Vargas Llosa’s three milestone novels are La Ciudad y Los Perros (The Time of the Hero), La Casa Verde (The Green House) and Conversación en la Catedral (Conversation in the Cathedral), though many critics agree that The War of the End of the World should also be included among these three. The author is famously known for considering this his most accomplished novel — an opinion shared by the Chilean novelist Roberto Bolaño, as well as the American critic Harold Bloom, who even includes the novel in what he calls the “Western canon.”

As he did later on with La Fiesta Del Chivo (The Feast of the Goat), Vargas Llosa tackles a huge number of characters and stories caught during a time of strife, interweaving these in way that gives us a picture of what it was to live in those times.[citation needed]

Characters

- Antônio Conselheiro

- The Little Blessed One

- The Lion of Natuba

- João Abade (Abbot João)

- The Dwarf

- Father Joaquim

- Baron de Canabrava

- Pajeú

- Rufino

- Galileo Gall

- Maria Quadrado

- Moreira César

- Jurema

- The Near-Sighted Journalist

- João Grande (Big João)

- Pires Ferreira

- Antônio Vilanova

- Antônio o Fogueteiro

|

||||||||||

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_War_of_the_End_of_the_World

THE WAR OF THE END OF THE WORLD

Mario Vargas Llosa; Translated by Helen Lane

Picador

Deep within the remote backlands of nineteenth-century Brazil lies Canudos, home to all the damned of the earth: prostitutes, bandits, beggars, and every kind of outcast. It is a place where history and civilization have been wiped away. There is no money, no taxation, no marriage, no census. Canudos is a cauldron for the revolutionary spirit in its purest form, a state with all the potential for a true, libertarian paradise–and one the Brazilian government is determined to crush at any cost.

In perhaps his most ambitious and tragic novel, Mario Vargas Llosa tells his own version of the real story of Canudos, inhabiting characters on both sides of the massive, cataclysmic battle between the society and government troops. The resulting novel is a fable of Latin American revolutionary history, an unforgettable story of passion, violence, and the devastation that follows from fanaticism.

http://us.macmillan.com/thewaroftheendoftheworld/mariovargasllosa

THE WAR OF THE END OF THE WORLD

The Secret Agent — Videos

The Secret Agent (David Suchet, Patrick Malahide, Peter Capaldi, 1992)

The Secret Agent

First US edition cover

|

|

| Author | Joseph Conrad |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Spy fiction |

| Publisher | Methuen & Co |

|

Publication date

|

September 1907 |

| Media type | Print (hardcover) |

| Pages | 442 |

The Secret Agent: A Simple Tale is a novel by Joseph Conrad, published in 1907.[1] The story is set in London in 1886 and deals with Mr. Verloc and his work as a spy for an unnamed country (presumably Russia).The Secret Agent is notable for being one of Conrad’s later political novels. In these later novels, Conrad has moved away from his former tales of seafaring.

The novel deals broadly with anarchism, espionage, and terrorism.[2] It also deals with exploitation of the vulnerable, particularly in Verloc’s relationship with his brother-in-law Stevie, who has an intellectual disability.

The Secret Agent was ranked the 46th best novel of the 20th century by Modern Library.[3]

Because of its terrorism theme, it was noted as “one of the three works of literature most cited in the American media” two weeks after the September 11 attacks.[4]

Plot summary

The novel is set in London in 1886 and follows the life of Mr. Verloc, a secret agent. Verloc is also a businessman who owns a shop which sells pornographic material, contraceptives, and bric-a-brac. He lives with his wife Winnie, his mother-in-law, and his brother-in-law, Stevie. Stevie has a mental disability, possibly autism,[5] which causes him to be very excitable; his sister, Verloc’s wife, attends to him, treating him more as a son than as a brother. Verloc’s friends are a group of anarchists of which Comrade Ossipon, Michaelis, and “The Professor” are the most prominent. Although largely ineffectual as terrorists, their actions are known to the police. The group produce anarchist literature in the form of pamphlets entitled F.P., an acronym for The Future of the Proletariat.

The novel begins in Verloc’s home, as he and his wife discuss the trivialities of everyday life, which introduces the reader to Verloc’s family. Soon after, Verloc leaves to meet Mr. Vladimir, the new First Secretary in the embassy of a foreign country. Although a member of an anarchist cell, Verloc is also secretly employed by the Embassy as an agent provocateur. Vladimir informs Verloc that from reviewing his service history he is far from an exemplary model of a secret agent and, to redeem himself, must carry out an operation – the destruction of Greenwich Observatory by a bomb explosion. Vladimir explains that Britain’s lax attitude to anarchism endangers his own country, and he reasons that an attack on ‘science’, which he claims is the current vogue amongst the public, will provide the necessary outrage for suppression. Verloc later meets with his friends, who discuss politics and law, and the notion of a communist revolution. Unbeknownst to the group, Stevie, Verloc’s brother-in-law, overhears the conversation, which greatly disturbs him.

The novel flashes forward to after the bombing has taken place. Comrade Ossipon meets The Professor, who discusses having given explosives to Verloc. The Professor then describes the nature of the bomb which he carries in his coat at all times: it allows him to press a button which will blow him up in twenty seconds, and those nearest to him. After The Professor leaves the meeting, he stumbles into Chief Inspector Heat. Heat is a policeman who is working on the case regarding a recent explosion at Greenwich, where one man was killed. Heat informs The Professor that he is not a suspect in the case, but that he is being monitored due to his terrorist inclinations and anarchist background. Knowing that Michaelis has recently moved to the countryside to write a book, the Chief Inspector informs the Assistant Commissioner that he has a contact, Verloc, who may be able to assist in the case. The Assistant Commissioner shares some of the same high society acquaintances with Michaelis and is chiefly motivated by finding the extent of Michaelis’s involvement in order to assess any possible embarrassment to his connections. He later speaks to his superior, Sir Ethelred, about his intentions to solve the case alone, rather than rely on the effort of Chief Inspector Heat.

The novel then flashes back to before the explosion, taking the perspective of Winnie Verloc and her mother. At home, Mrs. Verloc’s mother informs the family that she wishes to move out of the house. Mrs. Verloc’s mother and Stevie use a hansom which is driven by a man with a hook in the place of his hand. The journey greatly upsets Stevie, as the driver’s tales of hardship coupled with his menacing hook scare him to the point where Mrs. Verloc must calm him down. On Verloc’s return from a business trip to the continent, his wife tells him of the high regard that Stevie has for him and she implores her husband to spend more time with Stevie. Verloc eventually agrees to go for a walk with Stevie. After this walk, Mrs. Verloc notes that her husband’s relationship with her brother has improved. Verloc then tells his wife that he has taken Stevie to go and visit Michaelis, and that Stevie would stay with him in the countryside for a few days.

As Verloc is talking to his wife about the possibility of emigrating to the continent, he is paid a visit by the Assistant Commissioner. Shortly thereafter, Chief Inspector Heat arrives to speak with Verloc, without knowing that the Assistant Commissioner had left with Verloc earlier that evening. The Chief Inspector tells Mrs. Verloc that he had recovered an overcoat at the scene of the bombing which had the shop’s address written on a label. Mrs. Verloc confirms that it was Stevie’s overcoat, and that she had written the address. On Verloc’s return, he realises that his wife knows her brother has been killed by Verloc’s bomb, and confesses what truly happened. A stunned Mrs. Verloc, in her anguish, then fatally stabs her husband.

After the murder, Mrs. Verloc flees her home, where she chances upon Comrade Ossipon, and begs him to help her. Ossipon assists her while confessing romantic feelings but secretly with a view to possess Mr Verloc’s bank account savings. They plan to run away and he aids her in taking a boat to the continent. However, her instability and the revelation of Mr. Verloc’s murder increasingly worry him, and he abandons her, taking Mr Verloc’s savings with him. He later discovers in a newspaper that a woman had disappeared, leaving behind her a wedding ring, before drowning herself in the English Channel.

Characters]

- Mr. Adolf Verloc: a secret agent who owns a shop in the Soho region of London. His primary characteristic, as described by Conrad, is indolence. He has been employed by an unnamed embassy to spy on revolutionary groups, which then orders him to instigate a terrorist act against the Greenwich Observatory. Their belief is that the resulting public outrage will force the English government to act more forcibly against emigre socialist and anarchist activists. He is part of an anarchist organisation that creates pamphlets under the heading The Future of the Proletariat. He is married to Winnie, and lives with his wife, his mother-in-law, and his brother-in-law, Stevie.

- Mrs. Winnie Verloc: Verloc’s wife. She cares deeply for her brother Stevie, who has the mental age of a young child. Of working class origins, her father was the owner of a pub. She is younger than her husband and married him not for love but to provide a home for her mother and brother. A loyal wife, she is deeply disturbed upon learning of the death of her brother due to her husband’s plotting, and kills him with a knife in the heart. She dies, presumably by drowning herself to avoid the gallows.

- Stevie: Winnie’s brother has the mental age of a young child and is very sensitive and is disturbed by notions of violence or hardship. His sister cares for him, and Stevie passes most of his time drawing numerous circles on pieces of paper. Verloc, exploiting both Stevie’s childlike simplicity and outrage at suffering, employs him to carry out the terrorist attack on the Greenwich Observatory. However, Stevie stumbles and the bomb explodes prematurely.

- Mrs. Verloc’s mother: Old and infirm, Mrs Verloc’s mother leaves the household to live in an almshouse, believing that two disabled people (herself and Stevie) are too much for Mr Verloc’s generosity. The widow of a publican, she spent most of her life working hard in her husband’s pub and believed Mr Verloc to be a gentleman because she thought he resembled patrons of business houses (pubs with higher prices, consequently frequented by higher classes).

- Chief Inspector Heat: a policeman who is dealing with the explosion at Greenwich. An astute and practical man who uses a clue found at the scene of the crime to trace events back to Verloc’s home. Although he informs his superior what he is planning to do with regards to the case, he is initially not aware that the Assistant Commissioner is acting without his knowledge. Heat knew Verloc before the bombing as Verloc had supplied information to Heat through the Embassy. Heat has contempt for anarchists who he regards as amateurs, as opposed to burglars who he regards as professionals.

- The Assistant Commissioner: of a higher rank than the Chief Inspector, he uses the knowledge gained from Heat to pursue matters personally, for reasons of his own. The Assistant Commissioner is married to a lady with influential connections. He informs his superior, Sir Ethelred, of his intentions, and tracks down Verloc before Heat can.

- Sir Ethelred: the Secretary of State (Home Secretary) to whom the Assistant Commissioner reports. At the time of the bombing he is busy trying to pass a bill regarding the nationalisation of fisheries through the House of Commons against great opposition. He is briefed by the Assistant Commissioner throughout the novel who he often admonishes to not go into detail.

- Mr. Vladimir: the First Secretary of an embassy of an unnamed country. Though his name might suggest that this is the Russian embassy, the name of the previous first secretary, Baron Stott-Wartenheim, is Germanic, as is that of Privy Councillor Wurmt, another official of this embassy. There is also the suggestion that Vladimir is not from Europe but Central Asia.[6] Vladimir thinks that the English police are far too soft on émigré socialist and anarchists, which are a real problem in his home country. He orders Verloc to instigate a terrorist act, hoping that the resulting public outrage will force the English government to adopt repressive measures.

- Michaelis: a member of Verloc’s group, and another anarchist. The most philosophical member of the group, his theories resemble those of Peter Kropotkin while some of his other attributes resemble Mikhail Bakunin.

- Comrade Alexander Ossipon: an ex-medical student, anarchist and member of Verloc’s group. He survives on the savings of various women he seduces, mostly working class. He is influenced by the theories on degeneracy of Cesare Lombroso. After Mr Verloc’s murder he initially helps, but afterwards abandons Winnie leaving her penniless on a train. He is later disturbed when he reads of her suicide and wonders if he will be able to seduce a woman again.

- Karl Yundt: a member of Verloc’s group, commonly referred to as an “old terrorist”.

- The Professor: another anarchist, who specialises in explosives. The Professor carries a flask of explosives in his coat that can be detonated within twenty seconds of him squeezing an india rubber ball in his pocket. The police know this and keep their distance. The most nihilistic member of the anarchists, the Professor feels oppressed and disgusted by the rest of humanity and has particular contempt for the weak. He dreams of a world where the weak are freely exterminated so that the strong can thrive. He supplies to Mr Verloc the bomb that kills Stevie.

Background: Greenwich Bombing of 1894

Conrad’s character, Stevie, is based on the French anarchist, Martial Bourdin, who died gruesomely in Greenwich Park when the explosives he carried prematurely detonated.[7] Bourdin’s motives remain a mystery as does his intended target, which may have been the Greenwich Observatory.[8] In the 1920 Author’s Note to the novel, Conrad recalls a discussion with Ford Madox Ford about the bombing:[9]

[…] we recalled the already old story of the attempt to blow up the Greenwich Observatory; a blood-stained inanity of so fatuous a kind that it was impossible to fathom its origin by any reasonable or even unreasonable process of thought. For perverse unreason has its own logical processes. But that outrage could not be laid hold of mentally in any sort of way, so that one remained faced by the fact of a man blown to bits for nothing even most remotely resembling an idea, anarchistic or other. As to the outer wall of the Observatory it did not show as much as the faintest crack. I pointed all this out to my friend who remained silent for a while and then remarked in his characteristically casual and omniscient manner: “Oh, that fellow was half an idiot. His sister committed suicide afterwards.” These were absolutely the only words that passed between us […].[10]

Major themes

Terrorism and anarchism

Terrorism and anarchism are intrinsic aspects of the novel, and are central to the plot. Verloc is employed by an agency which requires him to orchestrate terrorist activities, and several of the characters deal with terrorism in some way: Verloc’s friends are all interested in an anarchistic political revolution, and the police are investigating anarchist motives behind the bombing of Greenwich.

The novel was written at a time when terrorist activity was increasing. There had been numerous dynamite attacks in both Europe and the US, as well as several assassinations of heads of state.[11] Conrad also drew upon two persons specifically: Mikhail Bakuninand Prince Peter Kropotkin. Conrad used these two men in his “portrayal of the novel’s anarchists”.[12] However, according to Conrad’s Author’s Note, only one character was a true anarchist: Winnie Verloc. In The Secret Agent, she is “the only character who performs a serious act of violence against another”,[13] despite the F.P.’s intentions of radical change, and The Professor’s inclination to keep a bomb on his person.

Critics have analysed the role of terrorism in the novel. Patrick Reilly calls the novel “a terrorist text as well as a text about terrorism”[14] due to Conrad’s manipulation of chronology to allow the reader to comprehend the outcome of the bombing before the characters, thereby corrupting the traditional conception of time. The morality which is implicit in these acts of terrorism has also been explored: is Verloc evil because his negligence leads to the death of his brother-in-law? Although Winnie evidently thinks so, the issue is not clear, as Verloc attempted to carry out the act with no fatalities, and as simply as possible to retain his job, and care for his family.[15]

Politics

The role of politics is paramount in the novel, as the main character, Verloc, works for a quasi-political organisation. The role of politics is seen in several places in the novel: in the revolutionary ideas of the F.P.; in the characters’ personal beliefs; and in Verloc’s own private life. Conrad’s depiction of anarchism has an “enduring political relevance”, although the focus is now largely concerned with the terrorist aspects that this entails.[16] The discussions of the F.P. are expositions on the role of anarchism and its relation to contemporary life. The threat of these thoughts is evident, as Chief Inspector Heat knows F.P. members because of their anarchist views. Moreover, Michaelis’ actions are monitored by the police to such an extent that he must notify the police station that he is moving to the country.

The plot to destroy Greenwich is in itself anarchistic. Vladimir asserts that the bombing “must be purely destructive” and that the anarchists who will be implicated as the architects of the explosion “should make it clear that [they] are perfectly determined to make a clean sweep of the whole social creation.”[17] However, the political form of anarchism is ultimately controlled in the novel: the only supposed politically motivated act is orchestrated by a secret government agency.

Some critics, such as Fredrick R. Karl,[18] think that the main political phenomenon in this novel is the modern age, as symbolised by the teeming, pullulating foggy streets of London (most notably in the cab ride taken by Winnie and Stevie Verloc). This modern age distorts everything, including politics (Verloc is motivated by the need to keep his remunerative position, the Professor to some extent by pride), the family (symbolised by the Verloc household, in which all roles are distorted, with the husband being like a father to the wife, who is like a mother to her brother), even the human body (Michaelis and Verloc are hugely obese, while the Professor and Yundt are preternaturally thin). This extended metaphor, using London as a center of darkness much like Kurtz’s headquarters in Heart of Darkness,[19] presents “a dark vision of moral and spiritual inertia” and a condemnation of those who, like Mrs Verloc, think it a mistake to think too deeply.[20]

Literary significance and reception

Initially, the novel fared poorly in both the United Kingdom and the United States, selling only 3,076 copies between 1907 and 1914. The book fared slightly better in Britain, yet no more than 6,500 copies were pressed before 1914. Although sales increased after 1914, the novel never sold more than “modestly” throughout Conrad’s lifetime. The novel was released to favourable reviews, with most agreeing with the view of The Times Literary Supplement, that the novel “increase[d] Mr. Conrad’s reputation, already of the highest.”[21] However, there were detractors, who largely disagreed with the novel’s “unpleasant characters and subject”. Country Life magazine called the story “indecent”, whilst also criticising Conrad’s “often dense and elliptical style”.[21]

In modern times, The Secret Agent is considered to be one of Conrad’s finest novels. The Independent calls it “[o]ne of Conrad’s great city novels”[22] whilst The New York Times insists that it is “the most brilliant novelistic study of terrorism”.[23] It is considered to be a “prescient” view of the 20th century, foretelling the rise of terrorism, anarchism, and the augmentation of secret societies, such as MI5. The novel is on reading lists for both secondary school pupils and university undergraduates.[24][25][26]

Influence on Ted Kaczynski

The Secret Agent is said to have influenced the Unabomber—Theodore Kaczynski. Kaczynski was a great fan of the novel and as an adolescent kept a copy at his bedside.[27] He identified strongly with the character of “the Professor” and advised his family to readThe Secret Agent to understand the character with whom he felt such an affinity. David Foster, the literary attributionist who assisted the FBI, said that Kaczynski “seem[ed] to have felt that his family could not understand him without reading Conrad.”[28]

Kaczynski’s idolisation of the character was due to the traits that they shared: disaffection, hostility toward the world, and being an aspiring anarchist.[29] However, it did not stop at mere idolisation. Kaczynski used “The Professor” as a source of inspiration, and “fabricated sixteen exploding packages that detonated in various locations”.[30] After his capture, Kaczynski revealed to FBI agents that he had read the novel a dozen times, and had sometimes used “Conrad” as an alias.[31] It was discovered that Kaczynski had used various formulations of Conrad’s name – Conrad, Konrad, and Korzeniowski, Conrad’s original surname – to sign himself into several hotels in Sacramento. As in his youth, Kaczynski retained a copy of The Secret Agent, and kept it with him whilst living as a recluse in a hut in Montana.[11]

Adaptations

- In 1923 Conrad adapted the novel as a three-act drama of the same title.

- The novel formed the basis for Alfred Hitchcock‘s 1936 film, Sabotage, though many changes to the plot and characters were made. (Another 1936 Hitchcock film, Secret Agent, was based on short stories by W. Somerset Maugham.)

- A television adaptation of The Secret Agent was made in 1992, a three part BBC miniseries, with David Suchet as Verloc, and Cheryl Campbell as his wife Winnie. Verloc was transformed into a much more sympathetic character for this work, in which he deeply grieved for Stevie’s death.

- A 1996 film The Secret Agent, more faithful to the original novel, starred Bob Hoskins, Patricia Arquette and Gérard Depardieu.

- On 23 May 2006 the Feldkirch Festival premiered an opera based on the novel. Simon Wills wrote the music and libretto and Peter Kajlinger sang the main character, Mr.Verloc.

- A play adaptation of the novel was produced in 2007 by Alexander Gelman, the Artistic Director of Organic Theater Company in Chicago, IL. The play’s premiere took place on 18 April 2008.

- In January 2008, the play was staged in Italian by the Teatro Stabile di Genova of Genoa, under the direction of Marco Sciaccaluga.

- The Center for Contemporary Opera in New York presented the world premiere of a new opera by Michael Dellaira (music) and J D McClatchy (libretto), at the Kaye Playhouse at Hunter College on 18 March 2011. Amy Burton sang Winnie, Scott Bearden sang Verloc. It had its European premiere at the Armel International Opera Festival on 14 October 2011 in Szeged, Hungary, where the opera was broadcast live on the Arte Channel, and named the festival’s “Laureat.” Adrienn Miksch sang Winnie, Nicolas Rigas sang Verloc. The same production was reprised on 18 April 2012 at L’Opéra-Théâtre d’Avignon in Avignon, France. All productions were directed by Sam Helfrich and conducted by Sara Jobin.

- The Capitol City Opera Company of Atlanta presented the world premiere of The Secret Agent, an opera in two acts with music by Curtis Bryant and libretto by Allen Reichman at the Conant Center for Performing Arts at Oglethorpe University on 15 March 2013. Directed by Michael Nutter, the production featured soprano Elizabeth Claxton in the role of Winnie, baritone Wade Thomas as Verloc and tenor Timothy Miller as Ossipon. In this operatic treatment, originally completed in 2007 under the title The Anarchist, Winnie, discovering that she has been abandoned on the train, sings a final aria “Fooled Again.” Bryant quotes one measure from Puccini’s Tosca before Winnie leaps into the path of an oncoming train, ending her life and the opera.

See also

Joseph Conrad

| Joseph Conrad | |

|---|---|

1904

|

|

| Born | Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski 3 December 1857 Terekhove near Berdychiv, Kiev Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 3 August 1924 (aged 66) Bishopsbourne, England |

| Resting place | Canterbury Cemetery,Canterbury |

| Occupation | Novelist, short-story writer |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Citizenship | British |

| Period | 1895–1923: Modernism |

| Genre | Fiction |

| Notable works | The Nigger of the ‘Narcissus’(1897) Heart of Darkness (1899) Lord Jim (1900) Typhoon (1902) Nostromo (1904) The Secret Agent (1907) Under Western Eyes (1911) |

| Spouse | Jessie George |

| Children | Borys, John |

|

|

|

| Signature |  |

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) is regarded as one of the greatest novelists in English.[1] He was granted British nationality in 1886, but always considered himself a Pole.[2][note 1] Though he did not speak English fluently until he was in his twenties (and always with a marked accent), he was a master prose stylist who brought a distinctly non-English sensibility into English literature.[note 2][3] He wrote stories and novels, many with a nautical setting, that depict trials of the human spirit.

Joseph Conrad is considered an early modernist, though his works still contain elements of nineteenth-century realism.[4] His narrative style and anti-heroic characters[5] have influenced many authors, including T.S. Eliot,William Faulkner,[6] Graham Greene,[6] and more recently Salman Rushdie.[note 3] Many films have been adapted from, or inspired by, Conrad’s works.

Writing in the heyday of the British Empire, Conrad drew on his Polish heritage and on his experiences in the French and British merchant navies to create short stories and novels that reflect aspects of a European-dominated world, while profoundly exploring human psychology. Appreciated early on by literary critics, his fiction and nonfiction have since been seen as almost prophetic, in the light of subsequent national and international disasters of the 20th and 21st centuries.[7]

Contents

Life

Early years

Conrad’s writer father, Apollo Korzeniowski

Nowy Świat 47, Warsaw, where three-year-old Conrad lived with his parents in 1861. In front: a “Chopin’s Warsaw” bench.

Joseph Conrad was born on 3 December 1857 in Berdychiv, in a part of Ukraine that had belonged to the Kingdom of Poland before 1793 and was at the time of his birth under Russianrule.[8] He was the only child of Apollo Korzeniowski and his wife Ewa Bobrowska. The father was a writer, translator, political activist, and would-be revolutionary. Conrad was christenedJózef Teodor Konrad after his maternal grandfather Józef, his paternal grandfather Teodor, and the heroes (both named “Konrad”) of two poems by Adam Mickiewicz, Dziady andKonrad Wallenrod. He was subsequently known to his family as “Konrad”, rather than “Józef”.

Though the vast majority of the surrounding area’s inhabitants were Ukrainians, and the great majority of Berdychiv’s residents were Jewish, almost all the countryside was owned by the Polish szlachta (nobility), to which Conrad’s family belonged as bearers of the Nałęcz coat-of-arms.[9] Polish literature, particularly patriotic literature, was held in high esteem by the area’s Polish population.[10]:1

The Korzeniowski family played a significant role in Polish attempts to regain independence. Conrad’s paternal grandfather served under Prince Józef Poniatowski during Napoleon’s Russian campaign and formed his own cavalry squadron during the November 1830 Uprising.[11] Conrad’s fiercely patriotic father belonged to the “Red” political faction, whose goal was to re-establish the pre-partition boundaries of Poland, but which also advocated land reform and the abolition of serfdom. Conrad’s subsequent refusal to follow in Apollo’s footsteps, and his choice of exile over resistance, were a source of lifelong guilt for Conrad.[12][note 4]

Because of the father’s attempts at farming and his political activism, the family moved repeatedly. In May 1861 they moved to Warsaw, where Apollo joined the resistance against the Russian Empire. This led to his imprisonment in Pavilion X (Ten) of the Warsaw Citadel.[note 5] Conrad would write: “[I]n the courtyard of this Citadel – characteristically for our nation – my childhood memories begin.”[2]:17–19 On 9 May 1862 Apollo and his family were exiled to Vologda, 500 kilometres (310 mi) north of Moscow and known for its bad climate.[2]:19–20 In January 1863 Apollo’s sentence was commuted, and the family was sent to Chernihiv in northeast Ukraine, where conditions were much better. However, on 18 April 1865 Ewa died of tuberculosis.[2]:19–25

Apollo did his best to home-school Conrad. The boy’s early reading introduced him to the two elements that later dominated his life: in Victor Hugo‘s Toilers of the Sea he encountered the sphere of activity to which he would devote his youth; Shakespeare brought him into the orbit of English literature. Most of all, though, he read Polish Romantic poetry. Half a century later he explained that “The Polishness in my works comes fromMickiewicz and Słowacki. My father read [Mickiewicz’s] Pan Tadeusz aloud to me and made me read it aloud…. I used to prefer [Mickiewicz’s] Konrad Wallenrod [and] Grażyna. Later I preferred Słowacki. You know why Słowacki?… [He is the soul of all Poland]”.[2]:27

In December 1867, Apollo took his son to the Austrian-held part of Poland, which for two years had been enjoying considerable internal freedom and a degree of self-government. After sojourns in Lwów and several smaller localities, on 20 February 1869 they moved to Kraków (till 1596 the capital of Poland), likewise in Austrian Poland. A few months later, on 23 May 1869, Apollo Korzeniowski died, leaving Conrad orphaned at the age of eleven.[2]:31–34 Like Conrad’s mother, Apollo had been gravely ill with tuberculosis.

Tadeusz Bobrowski, Conrad’s uncle and mentor, to whom Conrad owed so much

The young Conrad was placed in the care of Ewa’s brother, Tadeusz Bobrowski. Conrad’s poor health and his unsatisfactory schoolwork caused his uncle constant problems and no end of financial outlays. Conrad was not a good student; despite tutoring, he excelled only in geography.[2]:43 Since the boy’s illness was clearly of nervous origin, the physicians supposed that fresh air and physical work would harden him; his uncle hoped that well-defined duties and the rigors of work would teach him discipline. Since he showed little inclination to study, it was essential that he learn a trade; his uncle saw him as a sailor-cum-businessman who would combine maritime skills with commercial activities.[2]:44–46 In fact, in the autumn of 1871, thirteen-year-old Conrad announced his intention to become a sailor. He later recalled that as a child he had read (apparently in French translation) Leopold McClintock‘s book about his 1857–59 expeditions in the Fox, in search of Sir John Franklin‘s lost ships Erebus and Terror.[note 6] He also recalled having read books by the American James Fenimore Cooper and the English Captain Frederick Marryat.[2]:41–42 A playmate of his adolescence recalled that Conrad spun fantastic yarns, always set at sea, presented so realistically that listeners thought the action was happening before their eyes.

In August 1873 Bobrowski sent fifteen-year-old Conrad to Lwów to a cousin who ran a small boarding house for boys orphaned by the 1863 Uprising; group conversation there was in French. The owner’s daughter recalled:

He stayed with us ten months… Intellectually he was extremely advanced but [he] disliked school routine, which he found tiring and dull; he used to say… he… planned to become a great writer…. He disliked all restrictions. At home, at school, or in the living room he would sprawl unceremoniously. He… suffer[ed] from severe headaches and nervous attacks…[2]:43–44

Conrad had been at the establishment for just over a year when in September 1874, for uncertain reasons, his uncle removed him from school in Lwów and took him back to Kraków.