Archive for September, 2019

Anthropology Fieldwork — I believe — Force Yourself — Act — Videos

Posted on September 17, 2019. Filed under: American History, Anthropology, Blogroll, British History, College, Culture, Documentary, Economics, Education, Enlightenment, European History, Freedom, history, Investments, Language, Law, Life, People, Philosophy, Photos, Psychology, Science, Social Sciences, Sociology, Wealth, Wisdom, Work, Writing | Tags: Anthropology Field Work, Didier Fassin, Ellen Isaacs, Ethnographic Film, Ethnography, Gurung village, Julien S. Bourrelle, Margaret Mead and Samoa, Michael Henderson, Nanook of the North, Saba Safdar, Tales From The Jungle Malinowski, Videos |

Doing Anthropology

Anthropology: 25 Concepts in Anthropology:

What is Cultural Anthropology? An Introduction by Jack David Eller

Why Cultural Anthropology is important

Anthropology Careers

Jobs for Cultural Anthropology Majors : Career Counseling

Cultural Anthropologist: Why Girls Should Consider a Career in Anthropology – Joanna Davidson Career

Why I chose to major in Anthropology

Is an Anthropology Major Worth It?

What should I do with my life? | Charlie Parker | TEDxHeriotWattUniversity

Why your major will never matter | Megan Schwab | TEDxFSU

An introduction to the discipline of Anthropology

Ethnography: Ellen Isaacs at TEDxBroadway

What is Ethnography and how does it work?

Understanding Ethnography

Ethnography and Theory with Didier Fassin – Conversations with History

Critique of Humanitarian Reason | Didier Fassin

How Culture Drives Behaviours | Julien S. Bourrelle | TEDxTrondheim

Everything you always wanted to know about culture | Saba Safdar | TEDxGuelphU

Corporate Anthropology: Michael Henderson at TEDxAuckland

Franz Boas – The Shackles of Tradition

What is ETHNOGRAPHIC FILM? What does ETHNOGRAPHIC FILM mean? ETHNOGRAPHIC FILM meaning & explanation

Seeing Anthropology – An Ethnographic Film

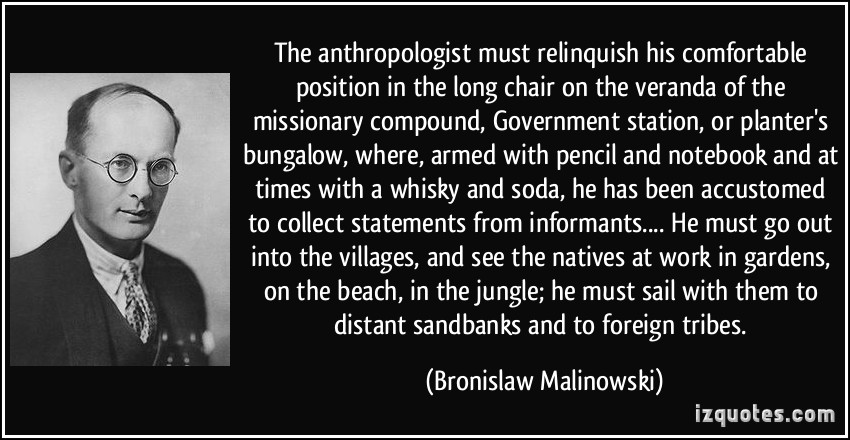

Tales From The Jungle Malinowski Part 1 of 6

Tales From The Jungle Malinowski Part 2 of 6

Tales From The Jungle Malinowski Part 3 of 6

Tales From The Jungle Malinowski Part 4 of 6

Tales From The Jungle Malinowski Part 5 of 6

Tales From The Jungle Malinowski Part 6 of 6

Nanook of the North (1922) – Classic Documentary

Coming of Age: Margaret Mead – IMPROVED COPY

Margaret Mead and Samoa – A difference of opinion

Tales from the Jungle: Margaret Mead

Margaret Mead, Herman Khan, William Irwin Thompson – nuclear power

Margaret Mead Interview

An interview of the anthropologist Sir Edmund Leach

Start with why — how great leaders inspire action | Simon Sinek | TEDxPugetSound

TEDxMaastricht – Simon Sinek – “First why and then trust”

The Skill of Humor | Andrew Tarvin | TEDxTAMU

Trust at Work: An Anthropological Approach: Joel Lesley Rozen at TEDxCarthage

Anthropological fieldwork in a Gurung village

The Men Who Hunted Heads

John Barker. Film 1. Childhood, Education and Anthropology in the Pacific

John Barker. Film 2. Fieldwork among the Maisin people and the Study of Christianity

Anthropological fieldwork; a personal account in Nepal

Marshall Sahlins: Anthropology

Full interview with Clifford Geertz – part one

Interview with Clifford Geertz, part two

Introducing Anthropology: Development and Culture Change – Associate Professor Greg Downey

Jim Freedman. Film 1. Loving New Worlds. Childhood and Education

Jim Freedman. Film 2. Doing a PhD in Anthropology in the United States and Fieldwork in Rwanda

Jim Freedman. Film 3. Exploring Localities of the World as a Consultant in Development Issues

Jim Freedman.Film 4. Quebec Anthropology and Black Communities of Nova Scotia

Jim Freedman. Film 5. Key issues in Development and Anthropology

Jim Freedman. Film 6. The World has changed. Anthropology, Development and Justice

How to escape education’s death valley | Sir Ken Robinson

Do schools kill creativity? | Sir Ken Robinson

V.O. Complete. “Teaching is an art”. Ken Robinson, educator and writer

In this video, the British educator and writer Ken Robinson talks about the importance of teachers. He thinks of teaching as an art and ensures that it is one of the most demanding professions that exist. Robinson, calls for conversation and dialogue as a fundamental part of the learning process. “The great teachers are students, and the great students are teachers,” he concludes.

Sir Ken Robinson Keynote Speaker at the 2018 Better Together: California Teachers Summit

At the 2018 Better Together: California Teachers Summit, Sir Ken Robinson, a leading education and creativity expert, delivered the keynote address from the Summit’s headquarters at Cal State Fullerton. Sir Ken’s thought-provoking speech challenged California’s teachers to transform our education system by building personal relationships and developing the appetite and curiosity of learners. Because, as he put it, “when the conditions are right, miracles happen everywhere.”

Marshall Sahlins talk on ‘The culture of Material Value and the Cosmography of Difference’

Cargo Cult

Anthropological fieldwork in Papua New Guinea, Part I: Moral and Scientific Considerations

Anthropological Fieldwork in Papua New Guinea, Part II: Moral and Scientific Considerations

Cultures of the World – 04 – Fieldwork And The Anthropological Method

How to stop screwing yourself over | Mel Robbins | TEDxSF

David Young. Film 1. Childhood, Education, Religion and Anthropology

Jason Paling

Introduction to Cultural Anthropology – Course Overview

Lecture 1 – Introduction to Anthropology

lecture 2

lecture 3

Lecture 4 Part 1-Language and Communication

Lecture 4 part 2

Lecture 6 – Getting Food

Lecture 7- Economics

Lecture 8 Sex and Marriage

Lecture 9 – Social Stratification

Lecture 10 – Family, Kinship, and Descent

lecture 11 – Grouping by Gender, Age, Common Interest, and Social Class

Lecture 12 – Politics, Power, and Violence

Lecture 13 – Religion and Magic

Lecture 14 – The Arts

Lecture 15 – The Processes of Change

lecture 16

Marshall Sahlins

Jump to navigationJump to search

|

Marshall Sahlins

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | December 27, 1930 (age 88) |

| Citizenship | American |

| Alma mater | University of Michigan Columbia University |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Anthropology |

| Institutions | University of Chicago |

| Doctoral students | David Graeber, Sherry Ortner |

| Influences | Karl Polanyi, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Morton Fried |

| Anthropology |

|---|

|

Types[show]

|

|

Key concepts[show]

|

|

Key theories[show]

|

|

Lists[show]

|

| Part of a series on |

| Economic, applied, and development anthropology |

|---|

|

Basic concepts[show]

|

|

Provisioning systems[show]

|

|

Case studies[show]

|

|

Related articles[show]

|

|

Major theorists[show]

|

| Social and cultural anthropology |

Marshall David Sahlins (/ˈsɑːlɪnz/ SAH-linz; born December 27, 1930) is an American anthropologist best known for his ethnographic work in the Pacific and for his contributions to anthropological theory. He is currently Charles F. Grey Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of Anthropology and of Social Sciences at the University of Chicago.[1]

Contents

Biography

Sahlins was born in Chicago. He was of Russian Jewish descent but grew up in a secular, non-practicing family. His family claims to be descended from Baal Shem Tov, a mystical rabbi considered to be the founder of Hasidic Judaism. Sahlin’s mother admired Emma Goldman and was a political activist as a child in Russia.[2]

Sahlins received his Bachelor of Arts and Master of Arts degrees at the University of Michigan where he studied with evolutionary anthropologist Leslie White. He earned his PhD at Columbia University in 1954. There his intellectual influences included Eric Wolf, Morton Fried, Sidney Mintz, and the economic historian Karl Polanyi.[3] After receiving his PhD, he returned to teach at the University of Michigan. In the 1960s he became politically active, and while protesting against the Vietnam War, Sahlins coined the term for the imaginative form of protest now called the “teach-in,” which drew inspiration from the sit-in pioneered during the civil rights movement.[4] In 1968, Sahlins signed the “Writers and Editors War Tax Protest” pledge, vowing to refuse tax payments in protest against the Vietnam War.[5] In the late 1960s, he also spent two years in Paris, where he was exposed to French intellectual life (and particularly the work of Claude Lévi-Strauss) and the student protests of May 1968. In 1973, he took a position in the anthropology department at the University of Chicago, where he is currently the Charles F. Grey Distinguished Service Professor of Anthropology Emeritus. His commitment to activism has continued throughout his time at Chicago, most recently leading to his protest over the opening of the University’s Confucius Institute[6][7] (which later closed in the fall of 2014).[8] On February 23, 2013, Sahlins resigned from the National Academy of Sciences to protest the call for military research for improving the effectiveness of small combat groups and also the election of Napoleon Chagnon. The resignation followed the publication in that month of Chagnon’s memoir and widespread coverage of the memoir, including a profile of Chagnon in the New York Times magazine.[9][10]

Alongside his research and activism, Sahlins trained a host of students who went on to become prominent in the field. One such student, Gayle Rubin, said: “Sahlins is a mesmerizing speaker and a brilliant thinker. By the time he finished the first lecture, I was hooked.”[11]

In 2001, Sahlins became publisher of Prickly Pear Pamphlets, which was started in 1993 by anthropologists Keith Hart and Anna Grimshaw, and was renamed Prickly Paradigm Press. The imprint specializes in small pamphlets on unconventional subjects in anthropology, critical theory, philosophy, and current events.[12]

His brother was the writer and comedian Bernard Sahlins (1922–2013).[13] His son, Peter Sahlins, is a historian.[14]

Work

Sahlins is known for theorizing the interaction of structure and agency, his critiques of reductive theories of human nature (economic and biological, in particular), and his demonstrations of the power that culture has to shape people’s perceptions and actions. Although his focus has been the entire Pacific, Sahlins has done most of his research in Fiji and Hawaii.

Sahlins (1972)[15]

Early work

Sahlins’s training under Leslie White, a proponent of materialist and evolutionary anthropology at the University of Michigan, is reflected in his early work. In his Evolution and Culture (1960), he touched on the areas of cultural evolution and neoevolutionism. He divided the evolution of societies into “general” and “specific”. General evolution is the tendency of cultural and social systems to increase in complexity, organization and adaptiveness to environment. However, as the various cultures are not isolated, there is interaction and a diffusion of their qualities (like technological inventions). This leads cultures to develop in different ways (specific evolution), as various elements are introduced to them in different combinations and on different stages of evolution.[1] Moala, Sahlins’s first major monograph, exemplifies this approach.

Contributions to economic anthropology

Stone Age Economics (1972) collects some of Sahlins’s key essays in substantivist economic anthropology. As opposed to “formalists,” substantivists insist that economic life is produced through cultural rules that govern the production and distribution of goods, and therefore any understanding of economic life has to start from cultural principles, and not from the assumption that the economy is made up of independently acting, “economically rational” individuals. Perhaps Sahlins’s most famous essay from the collection, “The Original Affluent Society,” elaborates on this theme through an extended meditation on “hunter-gatherer” societies. Stone Age Economics inaugurated Sahlins’s persistent critique of the discipline of economics, particularly in its Neoclassical form.

Contributions to historical anthropology

After the publication of Culture and Practical Reason in 1976, his focus shifted to the relation between history and anthropology, and the way different cultures understand and make history. Of central concern in this work is the problem of historical transformation, which structuralist approaches could not adequately account for. Sahlins developed the concept of the “structure of the conjuncture” to grapple with the problem of structure and agency, in other words that societies were shaped by the complex conjuncture of a variety of forces, or structures. Earlier evolutionary models, by contrast, claimed that culture arose as an adaptation to the natural environment. Crucially, in Sahlins’s formulation, individuals have the agency to make history. Sometimes their position gives them power by placing them at the top of a political hierarchy. At other times, the structure of the conjuncture, a potent or fortuitous mixture of forces, enables people to transform history. This element of chance and contingency makes a science of these conjunctures impossible, though comparative study can enable some generalizations.[16] Historical Metaphors and Mythical Realities (1981), Islands of History (1985), Anahulu (1992), and Apologies to Thucydides (2004) contain his main contributions to historical anthropology.

Islands of History sparked a notable debate with Gananath Obeyesekere over the details of Captain James Cook’s death in the Hawaiian Islands in 1779. At the heart of the debate was how to understand the rationality of indigenous people. Obeyesekere insisted that indigenous people thought in essentially the same way as Westerners and was concerned that any argument otherwise would paint them as “irrational” and “uncivilized”. In contrast Sahlins argued that each culture may have different types of rationality that make sense of the world by focusing on different patterns and explain them within specific cultural narratives, and that assuming that all cultures lead to a single rational view is a form of eurocentrism.[1]

Centrality of culture

Over the years, Sahlins took aim at various forms of economic determinism (mentioned above) and also biological determinism, or the idea that human culture is a by-product of biological processes. His major critique of sociobiology is contained in The Use and Abuse of Biology. His recent book, What Kinship Is—And Is Not picks up some of these threads to show how kinship organizes sexuality and human reproduction rather than the other way around. In other words, biology does not determine kinship. Rather, the experience of “mutuality of being” that we call kinship is a cultural phenomenon.[17]

Selected publications

- Social Stratification in Polynesia. Monographs of the American Ethnological Society, 29. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1958. (ISBN 9780295740829)

- Evolution and Culture, edited with Elman R Service. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1960. (ISBN 9780472087754)

- Moala: Culture and Nature on a Fijian Island. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1962.

- Tribesman. Foundations of American Anthropology Series. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1968.

- Stone Age Economics. New York: de Gruyter, 1972. (ISBN 9780415330077)

- The Use and Abuse of Biology: An Anthropological Critique of Sociobiology. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1976. (ISBN 9780472766000)

- Culture and Practical Reason. Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 1976. (ISBN 9780226733616)

- Historical Metaphors and Mythical Realities: Structure in the Early History of the Sandwich Islands Kingdom. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1981. (ISBN 9780472027217)

- Islands of History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985. (ISBN 9780226733586)

- Anahulu: The Anthropology of History in the Kingdom of Hawaii, with Patrick Vinton Kirch. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992. (ISBN 9780226733654)

- How “Natives” Think: About Captain Cook, for Example. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995. (ISBN 9780226733685)

- Culture in Practice: Selected Essays. New York: Zone Books, 2000. (ISBN 9780942299380)

- Waiting for Foucault, Still. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2002. (ISBN 9780971757509)

- Apologies to Thucydides: Understanding History as Culture and Vice Versa. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004. (ISBN 9780226734002)

- The Western Illusion of Human Nature. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2008. (ISBN 9780979405723)

- What Kinship Is–and Is Not. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012. (ISBN 9780226925127)

- Confucius Institute: Academic Malware. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2015. (ISBN 9780984201082)

- On Kings, with David Graeber, HAU, 2017 (ISBN 9780986132506)

Awards

- Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres (Knight in the Order of Arts and Letters), awarded by the French Ministry of Culture

- honorary doctorates from the Sorbonne and the London School of Economics

- Gordon J. Laing Prize for Culture and Practical Reason, awarded by the University of Chicago Press

- Gordon J. Laing Prize for How “Natives” Think, awarded by the University of Chicago Press

- J. I. Staley Prize for Anahulu, awarded by the School of American Research

See also

References

- ^ Jump up to:abc Moore, Jerry D. 2009. “Marshall Sahlins: Culture Matters” in Visions of Culture: an Introduction to Anthropological Theories and Theorists, Walnut Creek, California: Altamira, pp. 365-385.

- ^ “Interview with Marshall Sahlins”. Anthropological Theory. 8 (3): 319–328. 2008. doi:10.1177/1463499608093817. ISSN1463-4996.

- ^ Golub, Alex. “Marshall Sahlins”. Oxford Bibliographies Online. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ^ Sahlins, Marshall (February 2009). “The Teach-Ins: Anti-War Protest in the Old Stoned Age”. Anthropology Today. 25 (1): 3–5. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8322.2009.00639.x.

- ^ “Writers and Editors War Tax Protest” January 30, 1968, New York Post

- ^ Sahlins, Marshall (November 18, 2013). “China U”. The Nation. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ^ Redden, Elizabeth (April 29, 2014). “Rejecting Confucius Funding”. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ^ Redden, Elizabeth (September 26, 2014). “Chicago to Close Confucius Institute”. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ^ Serena Golden, “A Protest Resignation”, Inside Higher Ed, February 25, 2013.

- ^ David Price, “The Destruction of Conscience in the National Academy of Sciences: An Interview with Marshall Sahlins”, CounterPunch, February 26, 2013.

- ^ Rubin, Gayle. Deviations: Gayle Rubin Reader. Durham: Duke University Press, 2011, p. 24.

- ^ “Home”. Prickly Paradigm Press.

- ^ “Bernie Sahlins, co-founder of comedy troupe, dies at 90”.

- ^ Sahlins, Peter (2004). Unnaturally French: Foreign Citizens in the Old Regime and After.

- ^ Sahlins, Marshall (1972). The Original Affluent Society. A short essay at p. 129 in: Delaney, Carol Lowery, pp.110-133. Investigating culture: an experiential introduction to anthropology. Oxford: Blackwell, 2004. ISBN0-631-22237-5.

- ^ Golub, Alex (2013). Theory in Social and Cultural Anthropology: An Encyclopedia. Sage. p. 734. ISBN9781412999632.

- ^ Sahlins, Marshall (2013). What Kinship Is–And Is Not. The University of Chicago Press. ISBN9780226214290.

External links

- Faculty Page at the University of Chicago

- Annotated Bibliography, written by Alex Golub

- Interviews:

- Interviewed by Alan Macfarlane 6th June 2013 (video)

- Sahlins 101 hour-long video interview conducted by Matti Bunzl (former director of the Chicago Humanities Festival), November 2014

- De la modernité du projet anthropologique: Marshall Sahlins, l’histoire dialectique et la raison culturelle in French with audio excerpts in English

- In the Absence of the Metaphysical Field: An Interview with Marshall Sahlins

- About the controversy with Obeyesekere (See also Death of Cook article):

- Cook Was (a) a God or (b) Not a God, review of How ‘Natives’ Think About Captain Cook, for Example in the New York Times

- Cook’s Tour Revisited, The University of Chicago Magazine, April 1995.

- Articles available for free download:

- “The Original Affluent Society”

- “Poor Man, Rich Man, Big Man, Chief; Political Types in Melanesia and Polynesia”, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 5 (3): 285–303, 1963.

- Waiting for Foucault, Still, a pocket-sized book by Sahlins published in 2002 by Prickly Paradigm, now available for free online (in pdf)

- On the Anthropology of Levi-Strauss

- “On the Anthropology of Modernity: Or, Some Triumphs of Culture Over Despondency Theory” In Culture and Sustainable Development in the Pacific, edited by Anthony Hooper. Canberra, Australia: ANU E Press, 2005.

- Twin-born with greatness: the dual kingship of Sparta HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 1 (1): 63-101, 2011.

- Alterity and autochthony: Austronesian cosmographies of the marvelous. The 2008 Raymond Firth Lecture HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 2 (1): 131-160, 2012.

- On the culture of material value and the cosmography of riches, a distillation of Sahlins’s critique of economics from an anthropological perspective, HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 3 (2): 161-195, 2013.

- Dear colleagues—and other colleagues, Response to Symposium on What Kinship Is–And Is Not HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 3 (3): 337-347, 2013.

Ken Robinson (educationalist)

Jump to navigationJump to search

|

Sir Kenneth Robinson

|

|

|---|---|

Ken Robinson 2009

|

|

| Born | 4 March 1950 (age 69)

Liverpool, England

|

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Author, speaker, expert on education, education reformer, creativity and innovation |

| Website | sirkenrobinson.com |

Sir Kenneth Robinson (born 4 March 1950) is a British author, speaker and international advisor on education in the arts to government, non-profits, education and arts bodies. He was Director of the Arts in Schools Project (1985–89) and Professor of Arts Education at the University of Warwick (1989–2001), and is now Professor Emeritus at the same institution.[1] In 2003 he was knighted for services to the arts.[2]

Originally from a working class Liverpool family[3], Robinson now lives in Los Angeles with his wife and children[4].

Early life and education

Born in Liverpool, England to James and Ethel Robinson, Robinson is one of seven children from a working-class background. One of his brothers, Neil, became a professional footballer for Everton, Swansea City and Grimsby Town.[5] After an industrial accident, his father became quadriplegic. Robinson contracted polio at age four. He attended Margaret Beavan Special School due to the physical effects of polio then Liverpool Collegiate School (1961–1963), Wade Deacon Grammar School, Cheshire (1963–1968). He then studied English and drama (BEd) at Bretton Hall College of Education (1968–1972) and completed a PhD in 1981 at the University of London, researching drama and theatre in education.

Career

From 1985 to 1988, Robinson was Director of the Arts in Schools Project, an initiative to develop the arts education throughout England and Wales. The project worked with over 2,000 teachers, artists and administrators in a network of over 300 initiatives and influenced the formulation of the National Curriculum in England. During this period, Robinson chaired Artswork, the UK’s national youth arts development agency, and worked as advisor to Hong Kong’s Academy for Performing Arts.

For twelve years, he was professor of education at the University of Warwick, and is now professor emeritus. He has received honorary degrees from the Rhode Island School of Design, Ringling College of Art and Design, the Open University and the Central School of Speech and Drama, Birmingham City University and the Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts. He has been honoured with the Athena Award of the Rhode Island School of Design for services to the arts and education, the Peabody Medal for contributions to the arts and culture in the United States, the LEGO Prize for international achievement in education, and the Benjamin Franklin Medal of the Royal Society of Arts for outstanding contributions to cultural relations between the United Kingdom and the United States. In 2005, he was named as one of Time/Fortune/CNN‘s “Principal Voices”.[6] In 2003, he was made Knight Bachelor by the Queen for his services to the arts. He speaks to audiences throughout the world on the creative challenges facing business and education in the new global economies.[6]

In 1998, he led a UK commission on creativity, education and the economy and his report, All Our Futures: Creativity, Culture and Education, was influential. The Times said of it: “This report raises some of the most important issues facing business in the 21st century. It should have every CEO and human resources director thumping the table and demanding action”. Robinson is credited with creating a strategy for creative and economic development as part of the Peace Process in Northern Ireland, publishing Unlocking Creativity, a plan implemented across the region and mentoring to the Oklahoma Creativity Project. In 1998, he chaired the National Advisory Committee on Creative and Cultural Education.[7]

In 2001, Robinson was appointed Senior Advisor for Education & Creativity at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, which lasted at least until 2005.

A popular speaker at TED conferences, Robinson has given three presentations on the role of creativity in education, viewed via the TED website and YouTube over 80 million times (2017).[8][9] Robinson’s presentation “Do schools kill creativity?” is the most watched TED talk of all time (2017).[10][11][12] In April 2013, he gave a talk titled “How to escape education’s death valley”, in which he outlines three principles crucial for the human mind to flourish – and how current American education culture works against them.[13] In 2010, the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures & Commerce animated one of Robinson’s speeches about changing education paradigms.[14] The video was viewed nearly half a million times in its first week on YouTube and as of December 2017 has been viewed more than 15 million times.

Ideas on education

Robinson has suggested that to engage and succeed, education has to develop on three fronts. Firstly, that it should foster diversity by offering a broad curriculum and encourage individualisation of the learning process. Secondly, it should promote curiosity through creative teaching, which depends on high quality teacher training and development. Finally, it should focus on awakening creativity through alternative didactic processes that put less emphasis on standardised testing, thereby giving the responsibility for defining the course of education to individual schools and teachers. He believes that much of the present education system in the United States encourages conformity, compliance and standardisation rather than creative approaches to learning. Robinson emphasises that we can only succeed if we recognise that education is an organic system, not a mechanical one. Successful school administration is a matter of engendering a helpful climate rather than “command and control”.[13]

Criticism

|

|

This section of a biography of a living person does not include any references or sources. Please help by adding reliable sources. Contentious material about living people that is unsourced or poorly sourced must be removed immediately.

Find sources: “Ken Robinson” educationalist – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (May 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Robinson has responded to criticism in his 2015 book, Creative Schools: The Grassroots Revolution That’s Transforming Education, by encouraging his critics to look beyond his 18-minute TED talk to his many books and articles on the subject of education, in which he lays out plans for accomplishing his vision.

Writing

Learning Through Drama: Report of the Schools Council Drama Teaching (1977) was the result of a three-year national development project for the UK Schools Council. Robinson was principal author of The Arts in Schools: Principles, Practice, and Provision (1982), now a key text on arts and education internationally. He edited The Arts and Higher Education, (1984) and co-wrote The Arts in Further Education (1986), Arts Education in Europe, and Facing the Future: The Arts and Education in Hong Kong.

Robinson’s 2001 book, Out of Our Minds: Learning to be Creative (Wiley-Capstone), was described by Director magazine as “a truly mind-opening analysis of why we don’t get the best out of people at a time of punishing change.” John Cleese said of it: “Ken Robinson writes brilliantly about the different ways in which creativity is undervalued and ignored in Western culture and especially in our educational systems.”[15]

The Element: How Finding Your Passion Changes Everything, was published in January 2009 by Penguin. “The element” refers to the experience of personal talent meeting personal passion. He argues that in this encounter, we feel most ourselves, most inspired, and achieve to our highest level. The book draws on the stories of creative artists such as Paul McCartney, The Simpsons creator Matt Groening, Meg Ryan, and physicist Richard Feynman to investigate this paradigm of success.

Works

- 1977 Learning Through Drama: Report of The Schools Council Drama Teaching Project with Lynn McGregor and Maggie Tate. UCL. Heinemann. ISBN 0435185659

- 1980 Exploring Theatre and Education Heinmann ISBN 0435187813

- 1982 The Arts in Schools: Principles, Practice, and Provision,. Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. ISBN 0903319233

- 1984 The Arts and Higher Education. (editor with Christopher Ball). Gulbenkian and the Leverhulme Trust ISBN 0900868899

- 1986 The Arts in Further Education. Department of Education and Science.

- 1998 Facing the Future: The Arts and Education in Hong Kong, Hong Kong Arts Development Council ASIN B002MXG93U

- 1998 All Our Futures: Creativity, Culture, and Education (The Robinson Report). ISBN 1841850349

- 2001 Out of Our Minds: Learning to Be Creative. Capstone. ISBN 1907312471

- 2009 The Element: How Finding Your Passion Changes Everything (with Lou Aronica). Viking. ISBN 978-0670020478

- 2013 Finding Your Element: How To Discover Your Talents and Passions and Transform Your Life (with Lou Aronica). Viking. ISBN 9780670022380

- 2015 Creative Schools: The Grassroots Revolution That’s Transforming Education (with Lou Aronica). Penguin. ISBN 9780143108061

- 2018 You, Your Child, and School: Navigate Your Way to the Best Education Viking. ISBN 9780670016723

Awards

- 2003 Knight Bachelor for services to art

- 2004 Companionship of Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts[16]

- 2008 Governor’s Award for the Arts in Pennsylvania

- 2008 Gheens Foundation Creativity and Entrepreneurship Award

- 2008 George Peabody Medal[17]

- 2008 Benjamin Franklin Medal from the Royal Society of Arts[17]

- 2008 Honorary Degree from Birmingham City University[18]

- 2009 Honorary Doctor of Fine Arts from the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD)[19]

- 2011 Gordon Parks Award for Achievements in Education[20]

- 2012 Arthur C. Clarke Imagination Award[21]

- 2012 Honorary Doctor of Humane Letters from Oklahoma State University[22]

- Honorary Fellow of the Central School of Speech and Drama[23]

References …

- creativity? | Sir Ken Robinson | TED Talk”. TED.com. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Ken Robinson |

- Website and blog of Sir Ken Robinson

- Ken Robinson on Twitter

- Ken Robinson on IMDb

- Ken Robinson at TED

- In-depth interview on creativity

- Sir Ken Robinson interviewed on Conversations from Penn State

- IMNO Open Source Mentoring interview with Robinson

- Liverpool pupils interview Robinson, 2008

- London students interview Robinson, London International Music Show, 2008

- Podcast interview with DK from MediaSnackers, 2007

Dian Fossey — When you realize the value of all life, you dwell less on what is past and concentrate more on the preservation of the future — Videos

Posted on September 17, 2019. Filed under: Agriculture, American History, Anthropology, Blogroll, Books, College, Communications, Crisis, Culture, Documentary, Education, Employment, Heroes, history, liberty, Links, Literacy, media, Movies, Non-Fiction, People, Quotations, Raves, Raymond Thomas Pronk, Resources, Reviews, Social Sciences, Strategy, Video, Wealth, Wisdom, Work, Writing | Tags: Anthropology, Anthropology Field Work, Dian Fossey, Fossey & Galdikas, Goodall, Gorillas, Gorillas in The Mist, Jane Goodall, Man Of The Forest, Mary Galdikas, Mountain Gorillas, Mountain Gorillas' Survival, Orangutan, Who Killed Dian Fossey? |

The Lost Film of Dian Fossey DOCUMENTARY (2002)

Dian’s Active Conservation | Dian Fossey: Secrets in the Mist

Dian Fossey Narrates Her Life With Gorillas in This Vintage Footage | National Geographic

Dian Fossey, Digit’s death

Mountain Gorillas’ Survival: Dian Fossey’s Legacy Lives On | Short Film Showcase

Who Killed Dian Fossey? | Dian Fossey: Secrets in the Mist

Gorillas In The Mountain Mist [Gorilla Survival Documentary] | Real Wild

Dian Fossey: Secrets in the Mist | National Geographic

Mountain Gorillas’ Survival: Dian Fossey’s Legacy Lives On | Short Film Showcase

Dina Fossey Exibit Board Project

Dian Fossey: No One Loved Gorillas More

Dian Fossey Biography and Tribute by Grace Stevens

Maybe It Wasn’t Poachers? | Dian Fossey: Secrets in the Mist

Dian Fossey’s death

New documentary reveals who they believe killed gorilla campaigner dian fossey

In loving memory of Dian Fossey

Dian Fossey’s Grave Visited by Friends in Rwanda September 4, 2017

Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International 50th Anniversary Video

The Diana Fossey Gorilla Fund

Dian Fossey’s Early Days

Dian Fossey was born in San Francisco, Calif., in 1932. Her parents divorced when she was young, so Dian grew up with her mother and stepfather. By all accounts, she was an excellent student and was extremely interested in animals from a very young age. At age 6, she began horseback riding lessons and in high school earned a letter on the riding team.

Dian Fossey was born in San Francisco, Calif., in 1932. Her parents divorced when she was young, so Dian grew up with her mother and stepfather. By all accounts, she was an excellent student and was extremely interested in animals from a very young age. At age 6, she began horseback riding lessons and in high school earned a letter on the riding team.

When Dian enrolled in college courses at Marin Junior College, she chose to focus on business, following the encouragement of her stepfather, a wealthy businessman. She worked while in school, and at age 19, on the summer break following her freshman year of college, she went to work on a ranch in Montana. At the ranch, she fell in love with and developed an attachment to the animals, but she was forced to leave early when she contracted chicken pox.

Even so, the experience convinced Dian to follow her heart and return to school as a pre-veterinary student at the University of California. She found some of the chemistry and physics courses quite challenging, and ultimately, she turned her focus to a degree in occupational therapy at San Jose State College, from which she graduated in 1954.

Following graduation, Dian interned at various hospitals in California, working with tuberculosis patients. After less than a year she moved to Louisville, Ky., where she was hired as director of the occupational therapy department at Kosair Crippled Children Hospital. She enjoyed working with the people of Kentucky and lived outside the city limits in a cottage on a farm where the owners encouraged her to help work with the animals.

Following graduation, Dian interned at various hospitals in California, working with tuberculosis patients. After less than a year she moved to Louisville, Ky., where she was hired as director of the occupational therapy department at Kosair Crippled Children Hospital. She enjoyed working with the people of Kentucky and lived outside the city limits in a cottage on a farm where the owners encouraged her to help work with the animals.

Dian enjoyed her experience on the farm, but she dreamed of seeing more of the world and its abundant wildlife. A friend traveled to Africa and brought home pictures and stories of her exciting vacation. Once Dian saw the photos and heard the stories, she decided that she must travel there herself.

She spent many years longing to visit Africa and realized that if her dream were to be realized, she would have to take matters into her own hands. Therefore, in 1963, Dian took out a bank loan and began planning her first trip to Africa. She hired a driver by mail and prepared to set off to the land of her dreams.

Dian Fossey Tours Africa (1963)

It took Dian Fossey’s entire life savings, in addition a bank loan, to make her dream a reality. In September 1963, she arrived in Kenya. Her trip included visits to Kenya, Tanzania (then Tanganyika), Congo (then Zaire), and Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia). John Alexander, a British hunter, served as her guide. The route he planned included Tsavo, Africa’s largest national park; the saline lake of Manyara, famous for attracting giant flocks of flamingos; and the Ngorongoro Crater, well-known for its abundant wildlife.

The final two sites on her tour were Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania — the archaeological site of Louis and Mary Leakey — and Mt. Mikeno in Congo, where in 1959 American zoologist Dr. George Schaller carried out a pioneering study of the mountain gorilla. Schaller was the first person to conduct a reliable field study of the mountain gorillas, and his efforts paved the way for the research that would become Dian Fossey’s life work.

A Turning Point: Dian Fossey Visits Dr. Louis Leakey

“I believe it was at this time the seed was planted in my head, even if unconsciously, that I would someday return to Africa to study the gorillas of the mountains.” — “Gorillas in the Mist”

Visiting with Dr. Louis Leakey at Olduvai Gorge was an experience that Dian would later point to as a pivotal moment in her life. During their visit, Leakey talked to Dian about Jane Goodall’s work with chimpanzees in Tanzania, which at the time was only in its third year. He also shared with her his belief in the importance of long-term field studies with the great apes.

Visiting with Dr. Louis Leakey at Olduvai Gorge was an experience that Dian would later point to as a pivotal moment in her life. During their visit, Leakey talked to Dian about Jane Goodall’s work with chimpanzees in Tanzania, which at the time was only in its third year. He also shared with her his belief in the importance of long-term field studies with the great apes.

Leakey gave Dian permission to have a look around some newly excavated sites while she was at Olduvai. Unfortunately, in her excitement, she slipped down a steep slope, fell onto a recently excavated dig and broke her ankle. The impending climb that would take Dian to the mountain gorillas was at risk, but she would not be discouraged so easily. By her own account, after her fall, she was more resolved than ever to get to the gorillas.

Dian Fossey’s First Encounter with Gorillas

On Oct. 16, Dian visited the Travellers Rest, a small hotel in Uganda, close to the Virunga Mountains and their mountain gorillas. The hotel was owned by Walter Baumgartel, an advocate for gorilla conservation and among the first to see the benefits that tourism could bring to the area.

Baumgartel recommended that Dian meet with Joan and Alan Root, wildlife photographers from Kenya, who were collecting footage of the mountain gorillas for a photographic documentary. The Roots allowed Dian to camp behind their cabin and, after a few days, took her into the forest to search for gorillas. When they did come upon a group of gorillas and Dian was able to observe and photograph them, she developed a firm resolve to come back and study these beautiful creatures, As she describes in “Gorillas in the Mist”:

“It was their individuality combined with the shyness of their behavior that remained the most captivating impression of this first encounter with the greatest of the great apes. I left Kabara with reluctance but with never a doubt that I would, somehow, return to learn more about the gorillas of the misted mountains.”

Following her visit to the Virungas, Dian remained in Africa a while longer, staying with friends in Rhodesia. Upon arriving home in Kentucky, she resumed her work at Kosair Children’s Hospital, in order to repay the loan she had taken out for her trip to Africa – all the while dreaming of the day she would return.

Dian Fossey Sets Off to Study the Mountain Gorillas

As Dian Fossey continued her work in Kentucky at Kosair Children’s Hospital, she also found time to publish a number of articles and photographs from her Africa trip. These would serve her well in the spring of 1966, when a lecture tour brought Dr. Louis Leakey to Louisville. Dian joined the crowd and waited in line to speak with Leakey. When her turn came, she showed him some of the published articles.

This got his attention and during the conversation that followed, Leakey spoke to Dian about heading a long-term field project to study the gorillas in Africa. Leakey informed Dian that if she were to follow through, she would first have to have her appendix removed. Perhaps it was a sign of her strong will that she proceeded to do exactly that, only to later hear from Leakey that his suggestion was mainly his way of gauging her determination!

It was eight months before Leakey was able to secure the funding for the study. Dian used that time to finish paying off her initial trip to Africa and to study. She focused on a “Teach Yourself Swahili” grammar book and George Schaller’s books about his own field studies with the mountain gorillas. Saying goodbye to family, friends, and her beloved dogs proved difficult:

“There was no way that I could explain to dogs, friends, or parents my compelling need to return to Africa to launch a long-term study of the gorillas. Some may call it destiny and others may call it dismaying. I call the sudden turn of events in my life fortuitous.” — “Gorillas in the Mist”

In December 1966, Dian was again on her way to Africa. She arrived in Nairobi, and with the help of Joan Root, she acquired the necessary provisions. She set off for the Congo in an old canvas-topped Land Rover named “Lily,” that Dr. Leakey had purchased for her. On the way, Dian made a stop to visit the Gombe Stream Research Centre to meet Jane Goodall and observe her research methods with chimpanzees.

In December 1966, Dian was again on her way to Africa. She arrived in Nairobi, and with the help of Joan Root, she acquired the necessary provisions. She set off for the Congo in an old canvas-topped Land Rover named “Lily,” that Dr. Leakey had purchased for her. On the way, Dian made a stop to visit the Gombe Stream Research Centre to meet Jane Goodall and observe her research methods with chimpanzees.

Kabara: Beginnings (1966/1967)

Alan Root accompanied Dian Fossey from Kenya to the Congo and was instrumental in helping her obtain the permits she needed to work in the Virungas. He helped her recruit two African men who would stay and work with her at camp, as well as porters to carry her belongings and gear to the Kabara meadow. Root also helped her set up camp and gave her a brief introduction to gorilla tracking. It was only when he left, and after two days at Kabara that Dian realized just how alone she was. Soon, however, tracking the mountain gorillas would become her single focus, to the exclusion even of simple camp chores.

On her first day of trekking, after only a 10-minute walk, Dian was rewarded with the sight of a lone male gorilla sunning himself. The startled gorilla retreated into the vegetation as she approached, but Dian was encouraged by the encounter. Shortly thereafter, Senwekwe, an experienced gorilla tracker, who had worked with Joan and Alan Root in 1963, joined Dian, and the prospects for more sightings improved.

Slowly, Dian settled into life at Kabara. Space was limited; her 7-by-10-foot tent served as bedroom, bath, office and clothes-drying area (an effort that often seemed futile in the wet climate of the rainforest). Meals were prepared in a run-down wooden building and rarely included local fruits and vegetables, other than potatoes. Dian’s mainstay was tinned food and potatoes cooked in every way imaginable. Once a month, she would hike down the mountain to her Land Rover, “Lily,” and make the two-hour drive to the village of Kikumba to restock the pantry.

Senwekwe proved invaluable as a tracker and taught Dian much of what she came to know about tracking. With his help and considerable patience, she eventually identified three gorilla groups in her area of study along the slopes of Mt. Mikeno.

Dian Fossey Learns to Habituate the Gorillas

“The Kabara groups taught me much regarding gorilla behavior. From them I learned to accept the animals on their own terms and never to push them beyond the varying levels of tolerance they were willing to give. Any observer is an intruder in the domain of a wild animal and must remember that the rights of that animal supersede human interests.” — “Gorillas in the Mist”

Initially, the gorillas would flee into the vegetation as soon as Dian approached. Observing them openly and from a distance, over time, she gained their acceptance. She put the gorillas at ease by imitating regular activities like scratching and feeding, and copying their contentment vocalizations.

Initially, the gorillas would flee into the vegetation as soon as Dian approached. Observing them openly and from a distance, over time, she gained their acceptance. She put the gorillas at ease by imitating regular activities like scratching and feeding, and copying their contentment vocalizations.

Through her observations, she began to identify the individuals that made up each group. Like George Schaller before her, Dian relied heavily on the gorillas’ individual “noseprints” for purposes of identification. She sketched the gorillas and their noseprints from a distance and slowly came to recognize individuals within the three distinct groups in her study area. She learned much from their behavior and kept detailed records of their daily encounters.

Escape from Zaire

Dian Fossey worked tirelessly, every day carrying a pack weighing nearly 20 pounds (some days nearly double that) until the day she was driven from camp by the worsening political situation in Congo. On July 9, 1967, she and Senwekwe returned to camp to find armed soldiers waiting for them. There was a rebellion in the Kivu Province of Zaire and the soldiers had come to “escort” her down the mountain to safety.

She spent two weeks in Rumangabo under military guard until, on July 26, she was able to orchestrate her escape. She offered the guards cash if they would simply take her to Kisoro, Uganda, to register “Lily” properly and then bring her back. The guards could not resist and agreed to provide an escort. Once in Kisoro, Dian went straight to the Travellers Rest Hotel, where Walter Baumgärtel immediately called the Ugandan military. The soldiers from Zaire were arrested, and Dian was safe.

In Kisoro, Dian was interrogated and warned not to return to Zaire. After more questioning in Kigali, the capital of Rwanda, she finally flew back to Nairobi where she met with Dr. Leakey for the first time in seven months. There they decided, against the advice of the U.S. Embassy, that Dian would continue her work on the Rwandan side of the Virungas.

Dian Fossey founds Karisoke (1967)

“More than a decade later as I now sit writing these words at camp, the same stretch of alpine meadow is visible from my desk window. The sense of exhilaration I felt when viewing the heartland of the Virungas for the first time from those distant heights is as vivid now as though it had occurred only a short time ago. I have made my home among the mountain gorillas.” — “Gorillas in the Mist”

Much of Dian Fossey’s success in the study of mountain gorillas came from the help of people she met along the way. This would prove true once again as she moved her focus to Volcanoes National Park on the Rwandan side of the Virungas. In Rwanda, Dian met a woman named Rosamond Carr, who had lived in Rwanda for some years and was familiar with the country.

Carr introduced Dian to a Belgian woman, Alyette DeMunck, who was born in the Kivu Province of Zaire and lived in the Congo from an early age, remaining there with her husband until the political situation forced them to move to Rwanda. Alyette and Dian became fast friends, and Alyette became one of Dian’s staunchest supporters in the years to come.

Alyette DeMunck knew a great deal about Rwanda, its people, and their ways. She offered to help Dian find an appropriate site for her new camp and renewed study of the mountain gorillas of the Virungas. At first, Dian was disappointed to find the slopes of Mt. Karisimbi crowded with herds of cattle and frequent signs of poachers. She was rewarded, however, after nearly two weeks, when Dian reached the alpine meadow of Karisimbi, where she had a view of the entire Virunga chain of extinct volcanoes.

So it was, on Sept. 24, 1967, that Dian Fossey established the Karisoke Research Center — “Kari” for the first four letters of Mt. Karisimbi that overlooked her camp from the south and “soke” for the last four letters of Mt. Visoke, the slopes of which rose to the north, directly behind camp.

So it was, on Sept. 24, 1967, that Dian Fossey established the Karisoke Research Center — “Kari” for the first four letters of Mt. Karisimbi that overlooked her camp from the south and “soke” for the last four letters of Mt. Visoke, the slopes of which rose to the north, directly behind camp.

“Little did I know then that by setting up two small tents in the wilderness of the Virungas I had launched the beginnings of what was to become an internationally renowned research station eventually to be utilized by students and scientists from many countries.” — “Gorillas in the Mist”

Dian Fossey’s Work at Karisoke Gets Underway

Dian faced a number of challenges while setting up camp at Karisoke. Upon the departure of her friend Alyette, she was left with no interpreter. Dian spoke Swahili and the Rwandan men she had hired spoke only Kinyarwanda. Slowly, and with the aid of hand gestures and facial expressions, they learned to communicate. A second and very significant challenge was that of gaining “acceptance” among the gorillas in the area so that meaningful research could be done in close proximity to them. This would require that the gorillas overcome their shy nature and natural fear of humans.

George Schaller’s earlier work served as a basis for the techniques Dian would use to habituate the gorillas to her presence. Schaller laid out suggestions in his book, The Mountain Gorilla, which Fossey used to guide herself through the process of successfully habituating six groups of gorillas in the Kabara region.

George Schaller’s earlier work served as a basis for the techniques Dian would use to habituate the gorillas to her presence. Schaller laid out suggestions in his book, The Mountain Gorilla, which Fossey used to guide herself through the process of successfully habituating six groups of gorillas in the Kabara region.

At Karisoke, Dian continued to rely on Schaller’s work and the guidelines he set forth. She also came to depend on the gorillas’ natural curiosity in the habituation process. While walking or standing upright increased their apprehension, she was able to get quite close when she “knuckle-walked.” She would also chew on celery when she was near the groups, to draw them even closer to her. Through this process, she partially habituated four groups of gorillas in 1968.

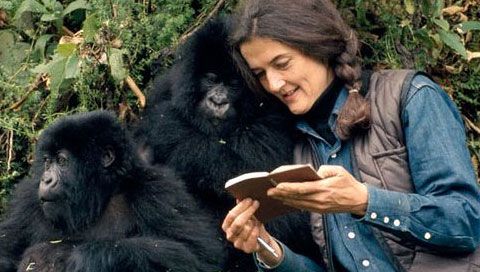

It was also in 1968 that the National Geographic Society sent photographer Bob Campbell to photograph her work. Initially, Dian saw his presence as an intrusion, but they would eventually become close friends. His photographs of Fossey among the mountain gorillas launched her into instant celebrity, forever changing the image of the gorillas from dangerous beasts to gentle beings and drawing attention to their plight.

Gaining Scientific Credentials

Dian Fossey never felt entirely up to the scientific aspects of studying the mountain gorillas because she did not have, in her view, adequate academic qualifications.

To rectify this, she enrolled in the department of animal behavior at Darwin College, Cambridge, in 1970. There, she studied under Dr. Robert Hinde, who had also been Jane Goodall’s supervisor. She traveled between Cambridge and Africa until 1974, when she completed her Ph.D.

Armed with the degree, she believed that she could be taken more seriously. It also enhanced her ability to continue her work, command respect, and most importantly, secure more funding.

Protecting the Gorillas

Even as Dian celebrated her daily achievements in collecting data and gaining acceptance among both the mountain gorillas and the world at large, she became increasingly aware of the threats the gorillas faced from poachers and cattle herders. Although gorillas were not usually the targets, they became ensnared in traps intended for other animals, particularly antelope or buffalo.

Dian fought both poachers and encroachment by herds of cattle through unorthodox methods: wearing masks to scare poachers, burning snares, spray-painting cattle to discourage herders from bringing them into the park, and, on occasion, taking on poachers directly, forcing confrontation.

She referred to her tactics as “active conservation,” convinced that without immediate and decisive action, other long-term conservation goals would be useless as there would eventually be nothing left to save.

These tactics were not popular among locals who were struggling to get by. Additionally, the park guards were not equipped to enforce the laws protecting the forest and its inhabitants.

As a last resort, Dian used her own funds to help purchase boots, uniforms, food and provide additional wages to encourage park wardens to be more active in enforcing anti-poaching laws. These efforts spawned the first Karisoke anti-poaching patrols, whose job was to protect the gorillas in the research area.

Dian Fossey and Digit

In the course of her years of research, Dian established herself as a true friend of the mountain gorilla. However, there was one gorilla with whom she formed a particularly close bond. Named Digit, he was roughly 5 years old and living in Group 4 when she encountered him in 1967. He had a damaged finger on his right hand (hence, the name) and no playmates his age in his group. He was drawn to her and her to him. Over time, a true friendship would form.

In the course of her years of research, Dian established herself as a true friend of the mountain gorilla. However, there was one gorilla with whom she formed a particularly close bond. Named Digit, he was roughly 5 years old and living in Group 4 when she encountered him in 1967. He had a damaged finger on his right hand (hence, the name) and no playmates his age in his group. He was drawn to her and her to him. Over time, a true friendship would form.

Tragically, on Dec. 31, 1977, Digit was killed by poachers. He died helping to defend his group, allowing them to escape safely. He was stabbed multiple times and his head and hands were severed. Eventually, there would be more deaths, including that of the dominant silverback Uncle Bert, and Group 4 would disband. It was then that Dian Fossey declared war on the poachers.

Digit had been part of a famous photo shoot with Bob Campbell and, as a result, had served as the official representative of the park’s mountain gorillas, appearing on posters and in travel bureaus throughout the world. After much internal debate, Dian used his celebrity and his tragic death to gain attention and support for gorilla conservation. She established the Digit Fund to raise money for her “active conservation” and anti-poaching initiatives. The Digit Fund would later be renamed the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International (Fossey Fund).

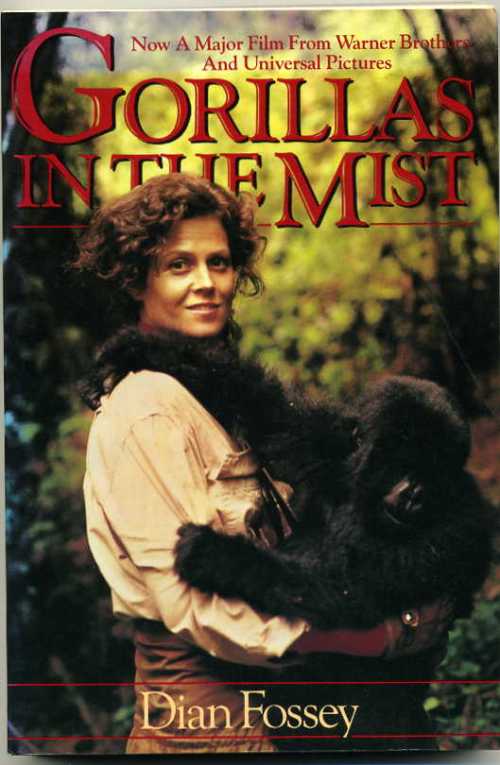

In 1980, Dian moved to Ithaca, New York, as a visiting associate professor at Cornell University. She used the time away from Karisoke to focus on the manuscript for her book, “Gorillas in the Mist.” Published in 1983, the book is an account of her years in the rainforest with the mountain gorillas. Most importantly, it underscores the need for concerted conservation efforts. The book was well received and, like the movie of the same name, remains popular to this day.

Dian Fossey’s Death (1985)

Dian had not been back in Rwanda long when, a few weeks before her 54th birthday, she was murdered. Her body was found in her cabin on the morning of Dec. 27, 1985. She was struck twice on the head and face with a machete. There was evidence of forced entry but no signs that robbery had been the motive.

Theories about Dian Fossey’s murder are varied but have never been fully resolved. She was laid to rest in the graveyard behind her cabin at Karisoke, among her gorilla friends and next to her beloved Digit.

Theories about Dian Fossey’s murder are varied but have never been fully resolved. She was laid to rest in the graveyard behind her cabin at Karisoke, among her gorilla friends and next to her beloved Digit.

“When you realize the value of all life, you dwell less on what is past and concentrate on the preservation of the future.” — “Gorillas in the Mist”

Continue Dian Fossey’s legacy by supporting the Fossey Fund’s gorilla protection work.

The Gorilla King–More on Dian Fossey and Her Research

It was from a small hut in Rwanda that researcher and conservationist Dian Fossey observed that while gorillas may sometimes act tough, they are really gentle giants.

Fossey is one of the most famous scientists in the world, but her path to greatness was a meandering one. While she had always been interested in animals, her bachelor’s degree was in occupational therapy. One year, after hearing stories and seeing pictures from a friend’s vacation in Africa, Fossey decided that she would visit there herself. In 1963, she gathered all of her savings and took out a three-year loan. She set a course for Africa, planning stops in Kenya, Tanzania, Congo, and Zimbabwe. She didn’t know it yet, but this trip would change her life forever.

At Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, one of the final stops on her journey, Fossey met archaeologist Louis Leakey. During the visit, Dr. Leakey told Fossey of Jane Goodall’s research with chimps, which at that point had just barely begun. They also discussed the importance of long-term research on the great apes. Fossey later said that this meeting planted the idea in her head that she would one day return to study the gorillas of Africa.

Early Research

Fossey began her long-term study of mountain gorillas in 1966, eventually establishing her “Karisoke” Research Center camp on Sept. 24, 1967, in an area between Mt. Visoke and Mt. Karisimbi, merging the names of the two volcanoes to create the name “Karisoke.”

She lived among the mountain gorillas for nearly 20 years keeping detailed journals to record everything she observed, and forging close relationships with individual gorillas as she gained their trust. She shared her thoughts and the results of her findings with the world, teaching us that gorillas are not monsters but social beings full of curiosity and affection. Her work paved the way for international support of mountain gorilla conservation and research, but her life was tragically cut short as a result of her efforts. She was found murdered in her cabin in Karisoke on December 26, 1985.

In 1988, the life and work of Fossey were portrayed in a movie based on her book. In the film Gorillas in the Mist, Sigourney Weaver starred as Fossey and later became the honorary chairperson of what is now the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International.

The film started a wave of curiosity about mountain gorillas and started a whole new industry of “gorilla tourism,” which has been a financial boon for conservation efforts, as well as a deterrent against poachers fearful of being discovered.

Fossey and Other Close Encounters

Just last year, in the Bwindi National Park in Uganda, a group of eight tourists quietly observed a family of mountain gorillas just a few yards away. After fifty-five minutes, a large male approached one of the tourists and gave him a big “high-five.”

“The gorilla probably approached him because he had a lot of body hair,” said Chuck Nichols, who ran the two-week gorilla tour in Uganda. Nichols owns a tour company based in Moab, Utah that specializes in small-group adventure tours around the world.

“The gorillas are not scary,” Nichols said, explaining that, actually, he has to make sure the gorillas are not the ones running scared. “A tracker must accompany the group, and people are only allowed to observe the gorillas for one hour,” he said. He also makes sure the groups are healthy since he does not want to stand the chance of passing on infectious diseases to the animals.

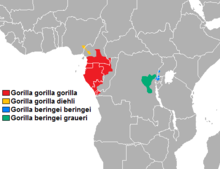

Sadly, these peaceful animals may not survive into the next century. Ape conservationists say time is running out, as there are only about 720 mountain gorillas left in the world, and the majority of gorilla populations are plummeting.

From the beginning, Fossey focused attention on the gorillas’ plight and saw clearly that they were doomed unless people could learn how to share forest resources with these great apes. She understood that they needed our protection if they were to survive, and gave her life in the struggle to protect them from poachers.

Like Fossey, biologists are becoming activists by necessity and are putting their lives on the line to save these great apes. In fact, conservation professionals and many national park staff have lost their lives in the course of duty because until now, their efforts have been poorly enforced. Today, ape conservation organizations, like the Great Apes Survival Project (GRASP) have come together to partner with Fossey’s Gorilla Fund in a last-ditch effort to unify existing conservation efforts.

In the mountains east of the Congo River Basin, human-transmitted pathogens have taken a heavy toll, and the hope is that GRASP will succeed in protecting the gorillas. Gorillas are closely related to humans and susceptible to the same diseases that we are; however, they have not developed the immunities to resist human diseases, making them vulnerable to infections that could spread and severely deplete an entire population.

Habituated gorilla groups (those that are visited by tourists) have the greatest risk, which is why tourists are not permitted to go near the gorillas if they feel sick. But, according to Melanie Virtue, a team leader for GRASP, this is hard to enforce, especially due to the amount of money that is spent to view these animals.

“You can imagine that a tourist traveling a great distance to see these animals, of which they have probably dreamed their entire lives, is going to be quite hesitant to say, ‘No, I am not feeling well and don’t want to endanger them,’” Virtue explains.

Today, the Karisoke Research Center that Fossey established is conducting a Tourism Impact Study, using both behavioral and physiological data (urine and fecal samples) to assess the impact of tourism on the Virunga mountain gorilla population.

“Almost certainly the biggest factor in the conservation success with this species has been the income they generate from gorilla tourism, so if you can afford it, going to see these amazing animals in the wild really is helping to ensure their survival,” said David Jay, senior officer of Born Free, an ape conservation organization that works with GRASP.

The future of these great apes will certainly depend on tourists’ interest in seeing these apes first-hand and that people show continued concern for their safety, according to Jay.

Fossey had the courage to follow gorillas among the steep ravines of a 14,000-foot volcano over 40 years ago, and so made it possible for all of us to follow in her footsteps.

Gorillas in the Mist The Story of Dian Fossey (1988)

Gorillas in the Mist • Behind the Scenes Featurette

Baby Mountain Gorilla | Gorillas Revisited with Sigourney Weaver | BBC

Destroying Snares | Gorillas Revisited with Sigourney Weaver | BBC

youtube=[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EK2yP1O2p-0]

Gorilla Manners | Gorillas Revisited with Sigourney Weaver | BBC

Sigourney Weaver Teaches Ellen How to Interact with Gorillas

Among Mountain Gorillas

Touched by a Wild Mountain Gorilla (short)

NEW – (short version) – An incredible chance encounter with a family of wild Mountain Gorillas in Uganda. Check blog.commonflat.com for more photos and background on this once in a lifetime experience.

Mountain Gorilla: A Shattered Kingdom! | Real Wild

Titus Gorilla King documentary english in HD part 1

Titus Gorilla King documentary english in HD part 2

Titus Gorilla King documentary english in HD part 3

Gorillas and Wildlife of Uganda HD

Saving Mountain Gorillas, for NTV Kenya

When Mountain Gorillas Attack

Gorillas – Kings of the jungle

Goodall, Fossey & Galdikas: Great Minds

One of “Leakey’s Angels”: Galdikas’ Quest to Save the Red Ape (Birute Galdikas)

Orangutan – Man Of The Forest HD

Orangutan National Geographic Documentary HD

Saving Baby Orangutans From Smuggling | Foreign Correspondent

Dr. Birute’ Mary Galdikas speaks at CWU

Gorilla Documentary – Gorillas: 98.6% Human | Explore Films

Heart-warming moment Damian Aspinall’s wife Victoria is accepted by wild gorillas OFFICIAL VIDEO

Dian Fossey

Jump to navigationJump to search

|

Dian Fossey

|

|

|---|---|

Dian Fossey in November 1984

|

|

| Born | January 16, 1932

San Francisco, California, U.S.

|

| Died | c. December 26, 1985 (aged 53) |

| Cause of death | Murder |

| Resting place | Karisoke Research Center |

| Citizenship | United States |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | Study and conservation of the mountain gorilla |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | The behaviour of the mountain gorilla (1976) |

| Doctoral advisor | Robert Hinde |

| Influences | |

Dian Fossey (/daɪˈæn/; January 16, 1932 – c. December 26, 1985) was an American primatologist and conservationist known for undertaking an extensive study of mountain gorilla groups from 1966 until her 1985 murder.[1] She studied them daily in the mountain forests of Rwanda, initially encouraged to work there by paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey. Gorillas in the Mist, a book published two years before her death, is Fossey’s account of her scientific study of the gorillas at Karisoke Research Center and prior career. It was adapted into a 1988 film of the same name.[2]

Fossey was one of the foremost primatologists in the world, a member of the so-called “Trimates”, a group formed of prominent female scientists originally sent by Leakey to study great apes in their natural environments, along with Jane Goodall who studied chimpanzees, and Birutė Galdikas, who studied orangutans. [3][4]

During her time in Rwanda, she actively supported conservation efforts, strongly opposed poaching and tourism in wildlife habitats, and made more people acknowledge sapient gorillas. Fossey and her gorillas were victims of mobbing; she was brutally murdered in her cabin at a remote camp in Rwanda in December 1985. It has been theorized that her murder was linked to her conservation efforts, probably by a poacher.

Contents

Life and career

Fossey was born in San Francisco, California, the daughter of Kathryn “Kitty” (née Kidd), a fashion model, and George E. Fossey III, an insurance agent.[2] Her parents divorced when she was six.[5] Her mother remarried the following year, to businessman Richard Price. Her father tried to keep in full contact, but her mother discouraged it, and all contact was subsequently lost.[6] Fossey’s stepfather, Richard Price, never treated her as his own child. He would not allow Fossey to sit at the dining room table with him or her mother during dinner meals.[7] A man adhering to strict discipline, Richard Price offered Fossey little to no emotional support.[8] Struggling with personal insecurity, Fossey turned to animals as a way to gain acceptance.[9] Her love for animals began with her first pet goldfish and continued throughout her entire life.[7] At age six, she began riding horses, earning a letter from her school; by her graduation in 1954, Fossey had established herself as an equestrienne.

Education

Educated at Lowell High School, following the guidance of her stepfather she enrolled in a business course at the College of Marin. However, spending her summer on a ranch in Montana at age 19 rekindled her love of animals, and she enrolled in a pre-veterinary course in biology at the University of California, Davis. In defiance to her stepfather’s wishes that she attend a business school, Dian wanted to spend her professional life working with animals. As a consequence, Dian’s parents failed to give her any substantial amount of financial support throughout her adult life.[7] She supported herself by working as a clerk at White Front (a department store), doing other clerking and laboratory work, and laboring as a machinist in a factory.

Although Fossey had always been an exemplary student, she had difficulties with basic sciences including chemistry and physics, and failed her second year of the program. She transferred to San Jose State College, where she became a member of Kappa Alpha Theta sorority, to study occupational therapy, receiving her bachelor’s degree in 1954.[10] Initially following her college major, Fossey began a career in occupational therapy. She interned at various hospitals in California and worked with tuberculosis patients.[11] Fossey was originally a prizewinning equestrian, which drew her to Kentucky in 1955, and a year later took a job as an occupational therapist at the Kosair Crippled Children’s Hospital in Louisville.[12]

Her shy and reserved personality allowed her to work well with the children at the hospital.[13] Fossey became close with her coworker Mary White “Gaynee” Henry, secretary to the hospital’s chief administrator and the wife of one of the doctors, Michael J. Henry. The Henrys invited Fossey to join them on their family farm, where she worked with livestock on a daily basis and also experienced an inclusive family atmosphere that had been missing for most of her life.[6][14] During her free time she would pursue her love of horses.[15]

Interest in Africa

Fossey turned down an offer to join the Henrys on an African tour due to lack of finances,[6] but in 1963 she borrowed $8,000 (one year’s salary), took out her life savings[16] and went on a seven-week visit to Africa.[5] In September 1963, she arrived in Nairobi, Kenya.[11] While there, she met actor William Holden, owner of Treetops Hotel,[5] who introduced her to her safari guide, John Alexander.[5] Alexander became her guide for the next seven weeks through Kenya, Tanzania, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Rhodesia. Alexander’s route included visits to Tsavo, Africa’s largest national park; the saline lake of Manyara, famous for attracting giant flocks of flamingos; and the Ngorongoro Crater, well known for its abundant wildlife.[11] The final two sites for her visit were Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania (the archeological site of Louis and Mary Leakey); and Mt. Mikeno in Congo, where in 1959, American zoologist George Schaller had carried out a yearlong pioneering study of the mountain gorilla. At Olduvai Gorge, Fossey met the Leakeys while they were examining the area for hominid fossils. Leakey talked to Fossey about the work of Jane Goodall and the importance of long-term research of the great apes.[11]

Although Fossey had broken her ankle while visiting the Leakeys,[11] by October 16, she was staying in Walter Baumgartel’s small hotel in Uganda, the Travellers Rest. Baumgartel, an advocate of gorilla conservation, was among the first to see the benefits that tourism could bring to the area, and he introduced Fossey to Kenyan wildlife photographers Joan and Alan Root. The couple agreed to allow Fossey and Alexander to camp behind their own camp, and it was during these few days that Fossey first encountered wild mountain gorillas.[11] After staying with friends in Rhodesia, Fossey returned home to Louisville to repay her loans. She published three articles in The Courier-Journal newspaper, detailing her visit to Africa.[5][11]

Research in the Congo

Gorilla mother with cub in Virunga National Park in the Congo

When Leakey made an appearance in Louisville while on a nationwide lecture tour, Fossey took the color supplements that had appeared about her African trip in The Courier-Journal to show to Leakey, who remembered her and her interest in mountain gorillas. Three years after the original safari, Leakey suggested that Fossey could undertake a long-term study of the gorillas in the same manner as Jane Goodall had with chimpanzees in Tanzania.[7] Leakey lined up funding for Fossey to research mountain gorillas, and Fossey left her job to relocate to Africa.[17]

After studying Swahili and auditing a class on primatology during the eight months it took to get her visa and funding, Fossey arrived in Nairobi in December 1966. With the help of Joan Root and Leakey, Fossey acquired the necessary provisions and an old canvas-topped Land Rover which she named “Lily”. On the way to the Congo, Fossey visited the Gombe Stream Research Centre to meet Goodall and observe her research methods with chimpanzees.[11] Accompanied by photographer Alan Root, who helped her obtain work permits for the Virunga Mountains, Fossey began her field study at Kabara, in the Congo in early 1967, in the same meadow where Schaller had made his camp seven years earlier.[18] Root taught her basic gorilla tracking, and his tracker Sanwekwe later helped in Fossey’s camp. Living in tents on mainly tinned produce, once a month Fossey would hike down the mountain to “Lily” and make the two-hour drive to the village of Kikumba to restock.[11]

Fossey identified three distinct groups in her study area, but could not get close to them. She eventually found that mimicking their actions and making grunting sounds assured them, together with submissive behavior and eating of the local celery plant.[18] She later attributed her success with habituating gorillas to her experience working as an occupational therapist with autistic children.[7] Like George Schaller, Fossey relied greatly on individual “noseprints” for identification, initially via sketching and later by camera.[11]

Fossey had arrived in the Congo in locally turbulent times. Known as the Belgian Congo until its independence in June 1960, unrest and rebellion plagued the new government until 1965, when Lieutenant General Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, by then commander-in-chief of the national army, seized control of the country and declared himself president for five years during what is now called the Congo Crisis. During the political upheaval, a rebellion and battles took place in the Kivu Province. On July 9, 1967, soldiers arrived at the camp to escort Fossey and her research workers down, and she was interred at Rumangabo for two weeks. Fossey eventually escaped through bribery to Walter Baumgärtel’s Travellers Rest Hotel in Kisoro, where her escort was arrested by the Ugandan military.[11][19] Advised by the Ugandan authorities not to return to Congo, after meeting Leakey in Nairobi, Fossey agreed with him against US Embassy advice to restart her study on the Rwandan side of the Virungas.[11] In Rwanda, Fossey had met local American expatriate Rosamond Carr, who introduced her to Belgian local Alyette DeMunck; DeMunck had a local’s knowledge of Rwanda and offered to find Fossey a suitable site for study.[11]

Conservation work in Rwanda

Fossey established her research camp on the foothills of Mount Bisoke.

On September 24, 1967, Fossey founded the Karisoke Research Center, a remote rainforest camp nestled in Ruhengeri province in the saddle of two volcanoes. For the research center’s name, Fossey used “Kari” for the first four letters of Mount Karisimbi that overlooked her camp from the south, and “soke” for the last four letters of Mount Bisoke, the slopes of which rose to the north, directly behind camp.[11] Established 3,000 metres (9,800 ft) up Mount Bisoke, the defined study area covered 25 square kilometres (9.7 sq mi).[20] She became known by locals as Nyirmachabelli, or Nyiramacibiri, roughly translated as “The woman who lives alone on the mountain.”[21]